As an author of Regency novels, I consult a lot of 19th century sources to ensure that the details of my stories are accurate for the period. Naturally, not everything ends up in my stories – that would be far too boring for my readers – so I enjoy posting snippets of interesting facts here on my blog.

One such source of information for food of the era is A Complete System of Cookery on a Plan Entirely New by John Simpson, a Regency cook to the nobility. I have a facsimile copy of the second edition, published in 1816. Simpson was cook to the Marquis of Buckingham and therefore had experience of providing meals to the highest in the land, including the Prince of Wales. Something that Simpson reminds his readers of several times!

However, in the preface Simpson says that he has included more economical recipes suitable for much less wealthy households. Simpson understands that not everyone would be hosting banquets; he wants to appeal to all levels of domestic households… and to sell more books.

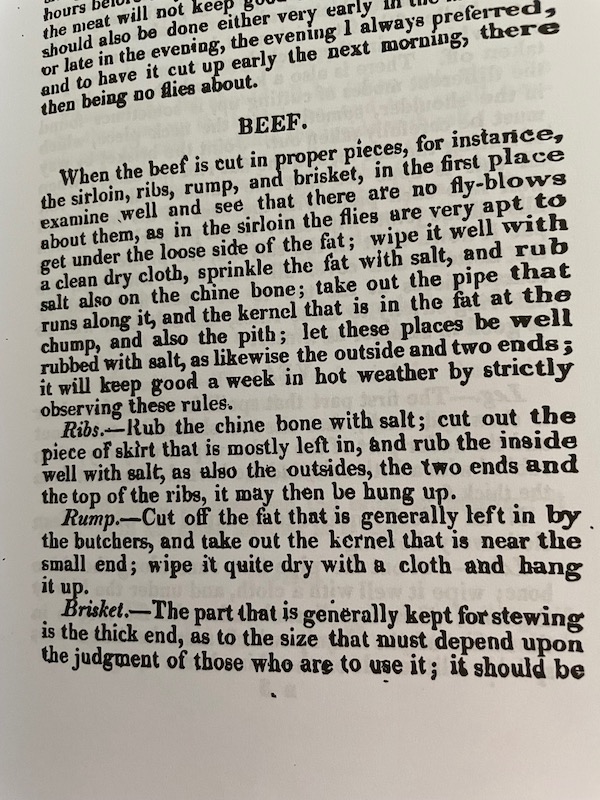

One important aspect that Simpson does not neglect is that of kitchen hygiene. I suppose if you are cooking meals for royalty, you certainly don’t want to be accused of poisoning them! He recommends that every morning, all the kitchen shelves and cupboards be scoured and washed clean with cold water. Any meat being stored should be changed to fresh plates. Also, any sauces and soups should be boiled up and placed in clean pans. One forgets how labour-intensive the life of a cook was before refrigeration.

Simpson reminds his readers to ensure that in summer, meat purchased from a butcher (if it is not killed at home) should be obtained as early in the day as possible. He suggests before six in the morning ‘otherwise when the heat of the day is advanced, it is almost impossible to prevent it from being fly-blown.’ Now, that is something that today’s home cook doesn’t generally have to worry about.

Even when the meat has been purchased, the household tasks aren’t completed. In the case of beef, if it is not to be immediately cooked, it should be thoroughly checked for flies, dried with a cloth, and excess fat removed. It should then be rubbed with salt before being hung up. By strictly following these rules, Simpson says that beef will keep well for a week in hot weather.

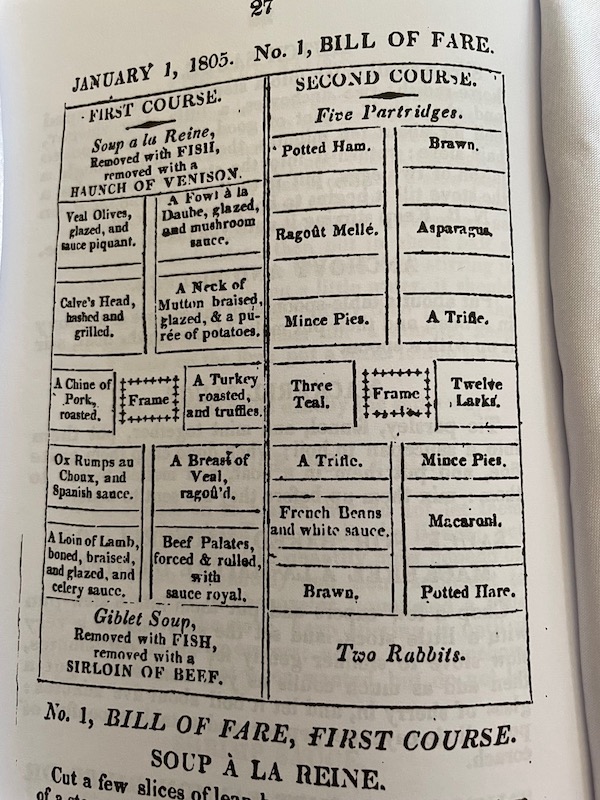

Having a sweet tooth, I was interested in his recipes for puddings and desserts, so I checked out the bill of fare for January 1st 1805, where two of my favourite dishes appeared. The recipe for trifle sounds extravagantly boozy, requiring a pint of Lisbon wine to soak the sponge biscuits or savoy cake that form the bottom layer, followed by a glass of brandy and a ‘few spoonfuls of ratafia’ to go in the custard. Finally, ‘about two glasses of white wine’ goes into the cream that tops the dish. That’s one trifle I’d like to try.

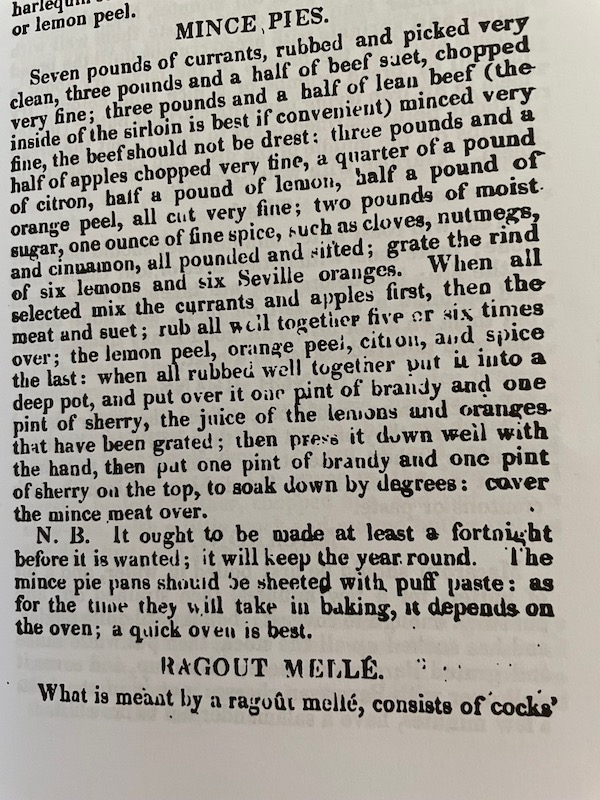

Mince pies, but not as we know them today, were also served at the same meal. As well as the usual mix of dried fruit, mixed peel, apples, oranges, lemons, and spices, three and a half pounds of lean beef ‘chopped very fine’ are also included. When all of this is mixed together it is put in a pot, and a pint of brandy, a pint of sherry, plus the juice from the fruits is added. But that’s not all. Everything is pressed down by hand, and then another pint each of brandy and sherry is added. Simpson notes that this mixture ought to be made at least a fortnight before it is needed and that it will keep for a year.

Simpson also includes examples of his mass catering, supplying menus for very large events. One such is for sixteen tables, with sixty people at each table. Each table was provided with 16 rounds of beef, 8 arch bones of beef, 8 briskets of beef, 8 sirloins of beef, 8 ribs of beef, 32 large meat pies (made of beef and mutton), 32 veal and lamb pies, 16 dishes of vegetables, 16 salads, and 6 large plum puddings. That must have been some feast.

Now one of the dishes I come across quite often in Regency novels is a lobster patty. These usually turn up during a ball scene, when the hero leads the heroine off to supper. I always wondered what they were. Well, Simpson calls them lobster patés and although he isn’t explicit, I understand that they are served in a small pastry case much like a vol au vent. Simpson’s recipe is to cut the lobster meat very small and add it to bechamel sauce with a few drops of anchovy essence and a little cayenne pepper. They sound delicious. I must remember to treat the characters in my forthcoming Regency novel, An Adventurer’s Contract, to some of these.

If you’re interested in reading Regency-set stories, check out my Amazon Author page here. Each book can be read as a standalone and all are free with Kindleunlimited. Spanish and Italian language editions are also available.

Images

William Henry Hunt, 1790–1864, British, A Dead Hare and a Cooked Lobster on a Bench, ca. 1827, Watercolor and brown ink over graphite on moderately thick, slightly textured, cream laid paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1975.3.867.

Bill of fare for January 1, 1805, p. 27, taken from A Complete System of Cookery on a Plan Entirely New John Atkinson, active 1770–1775, British, Kitchen Scene, 1771, Oil on canvas, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1981.25.23.

Instructions for beef, p. 4, taken from A Complete System of Cookery on a Plan Entirely New

Recipe for mince pies, p. 38, taken from A Complete System of Cookery on a Plan Entirely New

Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, Comforts of Bath: Gouty Gourmands at Dinner, 1798, Watercolor, pen and gray-brown ink, and graphite on medium, moderately textured, beige wove paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1975.3.42.