On a previous post I spoke about women who had occupations not usually associated with the ‘fairer sex’. Most of those employments, such as accompanying the army or working down the mines were undertaken out of economic necessity. Today I’m looking at ladies who don’t quite fit that category; in fact, at least one of them chose to live the way she did regardless of how unconventional she seemed to her contemporaries. Lets look at the first of my adventurous females.

Lady Florentia Wynch Sale (1790-1853) could be said to be the epitome of an adventurous female, though you’ve probably never heard of her. Florentia was the wife of Sir Robert Henry Sale (1782-1845), and she was with her husband during the First Anglo-Afghan War (1839-42). She kept a journal documenting her time there. Her descriptions of the British contingent’s departure from Kabul under extreme weather conditions and her subsequent capture and nine months’ captivity make gruesome reading.

‘The day was clear and frosty; the snow nearly a foot deep on the ground; the thermometer considerably below freezing point.’

According to Lady Sale, the party that left Kabul was made up of 4,500 fighting men and 12,000 followers. Many of the females on this journey not only had young children to care for but were also pregnant. The soldiers themselves were not in the best physical condition as the city of Kabul had been under siege for some time and they had been subsisting on half rations, while the poorer camp followers had been resorting to eating camels and ponies that had died from starvation.

Although they had been guaranteed a safe passage back to India, they were attacked almost immediately.

‘The whole road was covered with men, women, and children, lying down in the snow to die.’

Over the next couple of days, further attacks occurred, with Lady Sale herself being wounded.

‘I had fortunately only one ball in my arm; three others passed through my poshteen* near the shoulder without doing me any injury.’

She describes how another officer’s wife, Mrs Mainwaring, had the camel she and her three month old son were travelling on shot from under them. Mrs Mainwaring was then forced to keep up with the rest of the British party on foot.

‘She not only had to walk a considerable distance with her child in her arms through the deep snow, but had also to pick her way over the bodies of the dead, dying, and wounded, both men and cattle, and constantly to cross the streams of water, wet up to the knees, pushed and shoved about by men and animals, the enemy keeping up a sharp fire, and several persons being killed close to her.’

Lady Sale’s attitude towards the hardships she and the other women had to contend with was pragmatic.

‘It is true, we have been taken about the country; exposed to heat, cold, rain, &c.; but so were their own women. It was, and is, very disagreeable… Bugs have lately made their appearance; but not in great numbers: the flies torment us; and the musquitoes drive us half mad. But these annoyances, great as they are, are the results of circumstances which cannot be controlled.’

One gets the impression that Lady Sale was definitely an adventurous female and someone who could be relied on in a crisis.

Not all women in the past travelled in order to accompany their husbands; a number of them journeyed abroad because they wished to see more of the world. Mary Wollstonecraft (1759-1797), the second of my adventurous females, went to France in the belief that Continental women were not as confined to the domestic sphere as those in England. She believed that life away from England would give her the independence she craved. Another of her reasons for leaving the country was Henri Fuseli’s rejection of her proposal of a platonic relationship. Mary had pursued Fuseli even though he was already married.

Adventure didn’t only mean travel; Mary Wollstonecraft was adventurous in the way she broke societal norms. While in France she began a passionate affair with an American, Gilbert Imlay and in 1794 she gave birth to their daughter, Fanny. Sadly, the relationship didn’t last, and driven to despair because Imlay didn’t want her anymore, Mary attempted suicide. Fortunately, she was unsuccessful.

Returning to London, Mary renewed her acquaintance and fell in love with with William Godwin (1756-1836), a political philosopher and journalist. Defying convention again, Mary became pregnant by Godwin, and they married in early 1797. But in Godwin Mary had found someone who shared her views about independence. They did not set up home together but lived separately. Alas, their happiness did not last long; several days after the birth of their daughter, Mary succumbed to septicaemia and died.

Now we come to the third of my adventurous females. Jane Digby (1807-1881) was arguably even more scandalous than Mary Wollstonecraft. At the age of seventeen she married the widower Lord Ellenborough, who was twice her age. He was an ambitious politician and an acknowledged womaniser; his frequent absences from his beautiful young wife’s side soon led to inevitable consequences as the young Jane embarked on a series of extra-marital affairs. But it wasn’t until 1830, when she was still only in her early twenties, that her love affair with an Austrian prince led to divorce for Jane and Lord Ellenborough. The scandal of it all forced Jane to flee England for Europe.

But Jane’s scandalous and adventurous life didn’t end there. She went on to enjoy affairs with several members of European aristocracy, even marrying twice more. But it was when she was in her fifties that Jane’s adventurous life really took off. Travelling to Palmyra she fell in love with the young Arab chieftan who was escorting her caravan. He too fell in love with her and asked her to become his wife. Sheikh Medjuel el Mezrab became the love of her life and she spent her remaining years living in happiness as a respected and beloved member of her husband’s Bedouin tribe.

From being ‘the most notorious and profligate’ woman in London as she was called by diarist Thomas Creevey, Jane Digby el Mezrab became ‘loved and respected by all who knew her, especially the Arabs and Moslems to whom her kindness and charity were unlimited’ according to Mrs Reichardt, a missionary’s wife who befriended Jane in Damascus and who was with her in her final hours.

With remarkable women like these it is difficult to comprehend how the long-held perception of females as the weaker sex who should only be concerned with domestic matters was sustained well into the twentieth century. What do you think of my selection of adventurous females? Can you think of any others who might qualify for that description?

*poshteen is a sheepskin or fur pelisse

References

A journal of the disasters in Affghanistan, 1841-2 by Lady Sale, 1843, John Murray (available online courtesy of The Library of Congress:https://www.loc.gov/item/23000360/

Ladies of the Grand Tour by Brian Dolan, 2001, Harper Collins

A Scandalous Life: The Biography of Jane Digby el Mezrab, by Mary S. Lovell, 1995, Fourth Estate

Images

Florentia (née Wynch) Lady Sale by William James Ward, after Sir Thomas Lawrence

mezzotint, (after 1820)

NPG D4150 © National Portrait Gallery, London

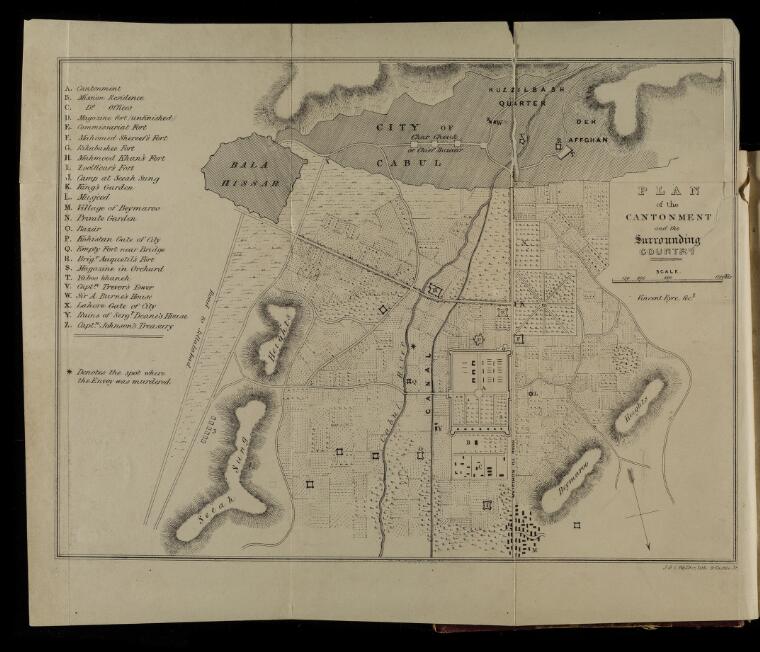

Plan of Cabul from ‘The military operations at Cabul, which ended in the retreat and destruction of the British Army, January 1842, with a journal of imprisonment in Afghanistan’, by Lieutenant Vincent Eyre, Bengal Artillery, late Deputy Commissary of Ordnance at Cabul (Kabul) Date: 1843 Reference: RAMC/690 Part of: Royal Army Medical Corps Muniments Collection, Wellcome Collection

Mary Wollstonecraft by John Opie oil on canvas, circa 1797 NPG 1237 © National Portrait Gallery, London

Jane Digby, Lady Ellenborough, by William Charles Ross, wikimedia