This week I had to make an emergency visit to the dentist. Fortunately, I didn’t require any major treatment, but I wondered what might have happened, if I’d been living in the early 1800s.

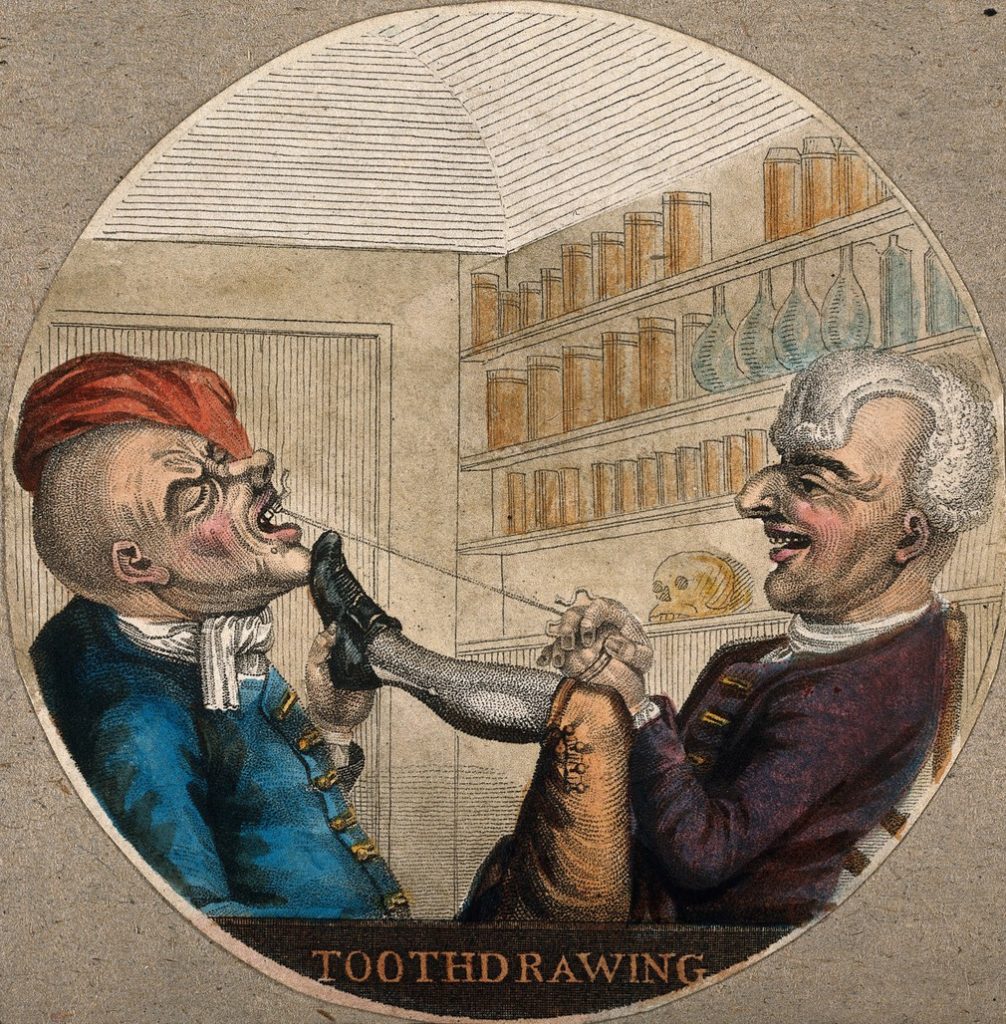

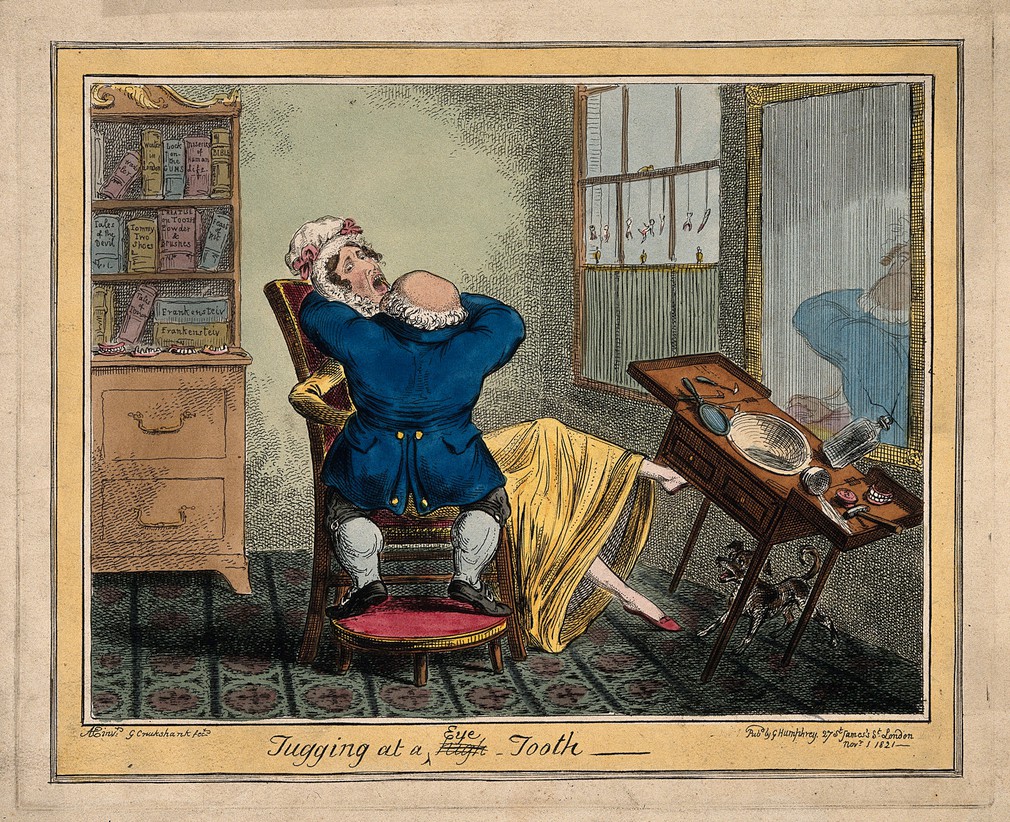

At the time, dentistry was not a regulated profession; in rural areas patients would go to the local blacksmith to have a tooth drawn – the only certain remedy open to them for toothache.

Le Chirurgien Dentiste (The Surgeon Dentist) a landmark publication in 1723, by Pierre Fauchard (1678 – 1761), a French physician, was the first complete scientific description of dentistry. For this, Fauchard is known as the father of modern dentistry. Fauchard laid down the foundations of good practice, identifying sugar as a major cause of tooth decay, developing instruments to deal with dental problems, and advocating the use of dental protheses for those who had lost their teeth.

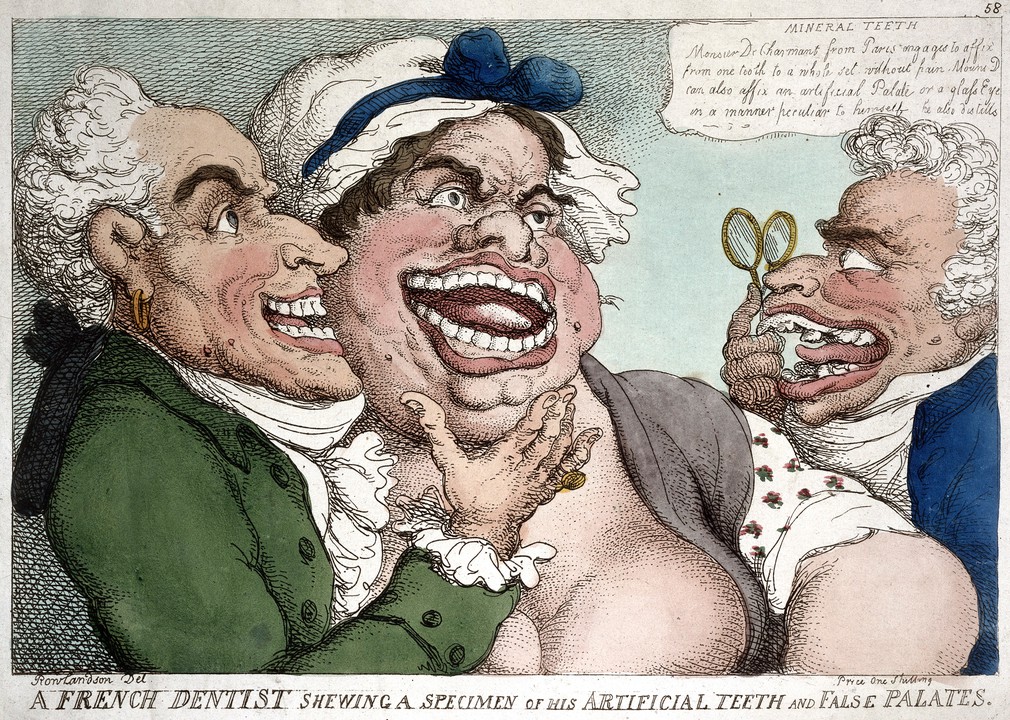

Despite the progress that came about by the spread of Fauchard’s ideas, the state of dentistry in early nineteenth century Britain was not good. According to the London Directory of 1838, there were one hundred and twenty individuals calling themselves Surgeon-Dentists, while according to the List of the Members of the Royal College of Surgeons, there were in actual fact only eight registered with the College.

A treatise (see below) written in 1837, by John Gray, a bona-fida surgeon-dentist, and a member of the Royal College of Surgeons, gives a good idea of the situation.

He begins by stating that there is a lot of quackery in the field of dentistry. He deplores the fact that so many practitioners are unskilled and do not have the knowledge that trained surgeons like himself have acquired.

He goes on to discuss the state of dental health in the population. ‘In the higher ranks of society is is scarcely possible to find a person of the age of twenty-four who has not lost some teeth, and so many of the remainder are carious and stopped with gold, that their mouths have some resemblance to the window of a jeweller’s shop.’ (p. 15)

He notes that there have been generational changes and comments that often parents have better teeth than their adult children. He puts this change down to the fact that many diseases, ‘always dangerous and often fatal’ were now treated with indifference because of improvements in medical and surgical science. In other words, the belief that medical science would have a cure, caused people to neglect their health until it was too late to do much about it.

His opinion on most medical practitioners is scathing: ‘provided that he be a person who is supposed fashionable, his fitness for profession is never questioned.’ (p. 16)

He goes on to discuss certain common practices in dentistry, for instance the removal of first (milk) teeth to make room for the second teeth, which he thinks is detrimental. This practice is something that Jane Austen mentions in a letter from 1813, describing her trip to a London dentist with her young nieces. She refers to the whole experience as ‘a disagreeable hour.’

Some of the practices that Gray writes about will seem familiar to present day readers, such as his recommendation to clean the teeth every day with a soft brush (William Addis manufactured the first modern toothbrush in 1780).

Another instruction is to avoid mercurial preparations ‘many persons are accustomed to administer blue pill and rhubarb for themselves and their families as familiarly as they would bread and cheese.’ (p.19) Mercury, although most commonly known as being used as a treatment for syphilis, when it was combined with other ingredients, was recommended as a remedy for such widely varied complaints as tuberculosis, constipation, parasites, childbirth pains, and toothache. Rhubarb today is still sold as a remedy for digestive complaints.

Filing teeth is another practice that Gray does not recommend. It was thought that by creating a space between the teeth to enable the use of a toothpick, assisted in keeping the teeth clean and healthy. In reality, and as Gray rightly understood, the enamel would be damaged by filing, causing decay to occur.

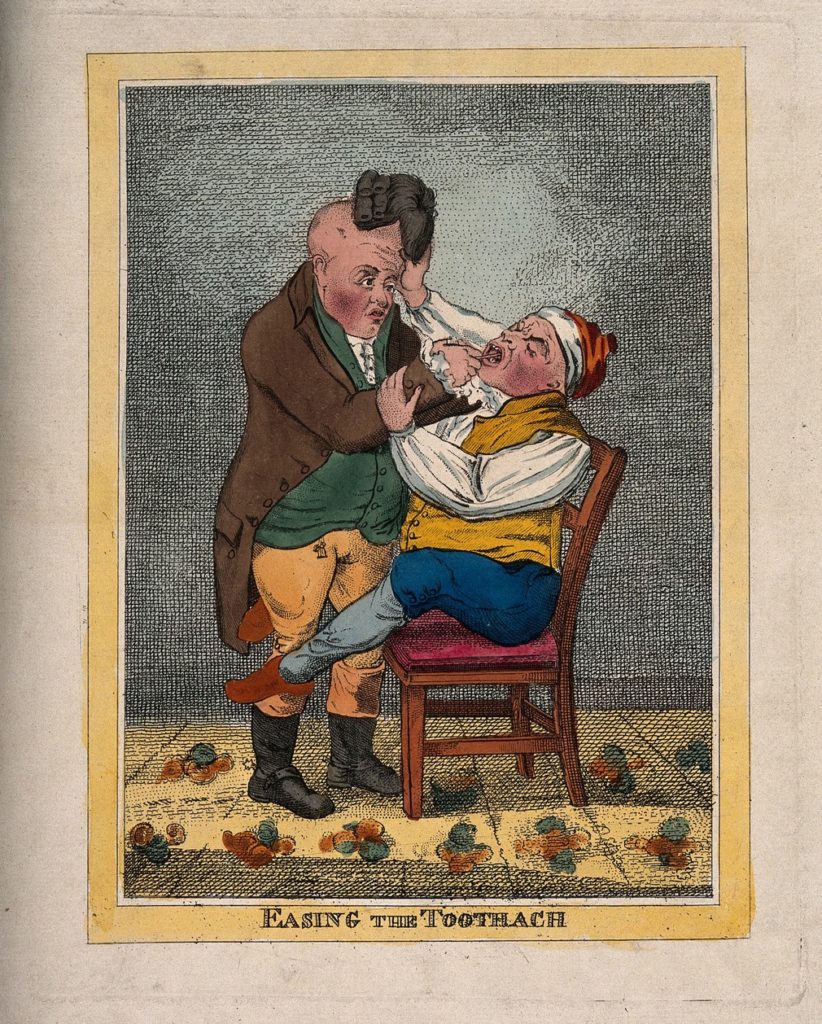

For toothache he recommends lint soaked in laudanum (tincture of opium) or paregoric (tincture of opium and camphor) to be applied to the tooth, as well as a low diet, vegetable laxatives, bathing the feet in warm water, and using means to promote perspiration. For severe cases, the mouth is to be held over hot water, and cloths soaked in the hot water, together with a handful of camomile flowers wrapped in them, should be applied to the cheek. The purpose of this treatment was to suppurate the gum and encourage the release of pus, considered to be the cause of the ache.

Where extraction is unavoidable, such as ache caused by a decayed tooth, Gray insists ‘the sooner it is extracted the better.’ (p. 24) He also states that a piece of ginger may be kept in the mouth for the pain, or suggests a hot wire is introduced into the hollow of the tooth to deaden the nerve. An early form of root canal work, perhaps? The hole in the tooth should then be stopped up with bees’ wax or gum mastic to shield the nerve.

Strangely perhaps to modern readers, a holistic approach is recommended. When someone is suffering from toothache, the tooth is not the only part of the body to be treated. For instance, he recommends that the feet must always be kept warm, and that due attention should be paid to the state of the patient’s bowels.

Although Gray observes that tooth problems are common during pregnancy, something which we now know a lot more about (and a reason why pregnant women are entitled to free dental care in the UK), he states categorically that pregnancy cannot be the cause ‘to attribute the loss of sound teeth to the fulfilment of a function highly favourable to health, would be to place nature in contradiction to herself.’ (p.25)

After this excellent survey of the state of the nation’s dental health, Gray gets to the real purpose of his treatise. He wants his fellow qualified surgeons to unite in common purpose against unqualified practitioners, in order to protect the public. He says it is only because surgeons generally dislike drawing teeth that the public are forced to resort to the services of unqualified tooth drawers.

He points out one of the main disadvantages of losing teeth; ‘How often is a fine face changed into an object of disgust from this cause alone!’ (p.49)

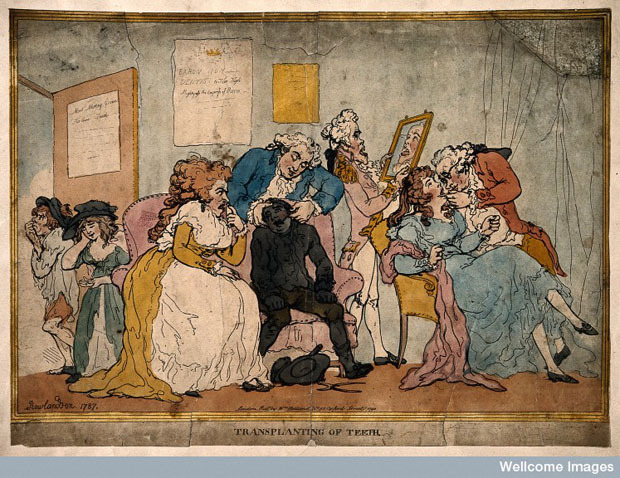

Of course here he is leading up to expounding the value of false teeth – particularly the ones he manufactures. By his method, a patient will endure no pain, no removal of teeth or stumps, and importantly, it will require no inconvenience ‘any more than if the article in question were an ordinary piece of dress.’ (p.49)

His dentures are held in place ‘by capillary attraction and the pressure of the atmosphere occasioning a natural adhesion to the gum only… the wearer soon becomes unconscious that he uses artificial teeth.’ (p. 50) The material he uses in their manufacture is the ‘tusk of the hippopatamus,(either with or without human teeth) (p. 50). According to Gray, this is the only substance that feels comfortable and congenial to the mouth.

I’m afraid that I’ll have to take his word for that. All I can say is that I’m happy that I didn’t need to visit the blacksmith this week.

References

Dental Practice; Or Observations on The Qualifications of the Surgeon-Dentist…, Gray, John, London, 1837

A Glasgow Dentist, an Edinburgh Legacy, Paul Geissler http://www.historyofdentistry.group/index_htm_files/2001Oct2.pdf

The Evolution of Dentistry, https://museumofhealthcare.wordpress.com/2013/03/08/the-evolution-of-dentistry/

This was so interesting. I didn’t know people made the connection between pregnancy and tooth problems so long ago!

Yes, that was surprising,Lydia,considering the general state of people’s teeth anyway. I wonder if Gray’s opinion that pregnancy itself had nothing to do with it was widespread. His idea that pregnancy was ‘highly favourable to health’ seems to ignore the fact of high maternal mortality too. Grim time to be a woman!