Here is my third and final post about Sir John Moore’s system of training. Today, I’m looking at drill.

Drill was an important feature of a soldier’s training. Recruits were initially taught this on an individual basis, then as they progressed, they were taught in squads, then companies and battalions.

Starting with close order drill, the soldiers were shown how to hold themselves, march, face, and wheel. A recruit learned how to stand at ease and at attention, and exercises were employed to improve the recruits’ carriage. It wasn’t until these drills were mastered that a recruit progressed onto marching.

Different sorts of steps were required for marching: the oblique step, stepping out, stepping short, mark time, changing feet, closing step, and back step. The Quick March was carried out at 108 paces per minute. ‘On the word “March” they step off with the left feet, keeping the body erect, and the arms steady down by the side, the hands just grazing the thigh.’

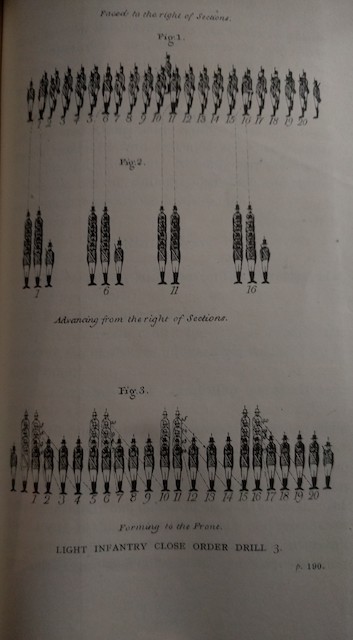

Once recruits mastered these they commenced drilling as part of a squad, learning how to wheel and advance and retire from the right or left of a line by files. Manoevres had specific names: wheeling backwards, wheeling on a movable pivot, and wheeling on the centre.

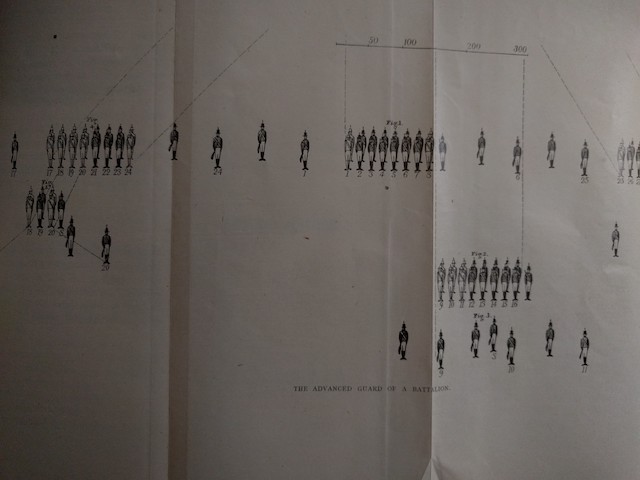

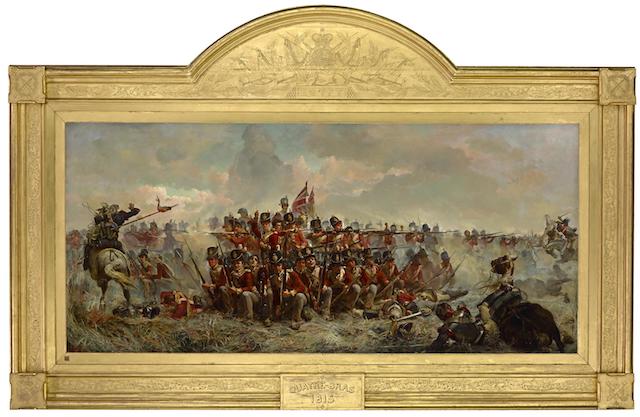

A step up from squad drill was battalion drill, when larger numbers of troops were taught to move in concert. The movements were based on three formations: the line, the column, and the square. To someone not familiar with military training it all sounds very complicated, but it does explain how large bodies of men were able to keep their heads and move quickly into position in the heat of battle.

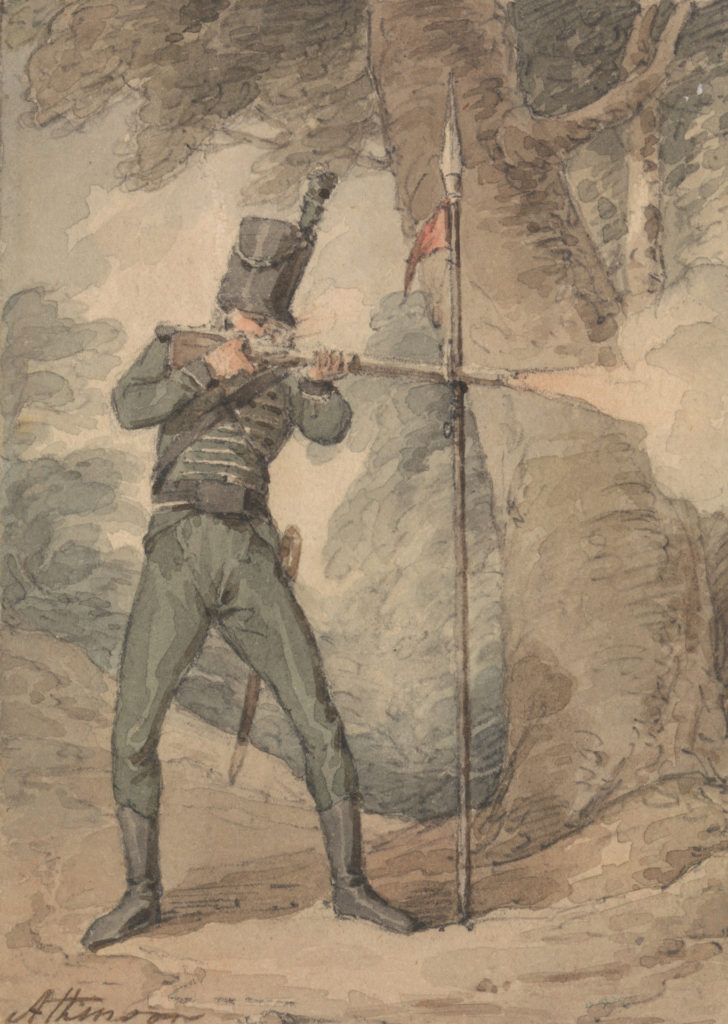

Musketry drill was another important skill that a soldier had to master. He was taught how to handle and load his weapon. Next came range practice, with the purpose of teaching each individual soldier to become a marksman. Speed of loading a weapon was important, but so was accuracy of shot. Rules were laid down as to the firing practice and careful records were kept of how many rounds were fired and where the bullets landed. The men were ranked according to their ability:

1st Class or bad shots

2nd Class or tolerably good shots – these men were awarded a small white cockade for their caps

3rd Class or marksmen – these men wore a small green cockade

Specific Light Infantry training included drills to improve mobility and quickness of movement.

The men were also taught how to take advantage of the terrain in which they found themselves, ‘to look out for their object of fire, and a place of security behind a rock, tree, or whatever else may be at hand.’ Skirmishers were trained to fire in all sorts of positions, from standing, kneeling, sitting, and lying down.

Because these men were expected to operate in a less cohesive formation to the main battalion, individual iniative was also encouraged, so that they could move around the field of action in directions that would ‘least impede (the battalion) and soonest leave it in a situation for firing or marching.’

The light drill that Moore taught at Shorncliffe training camp spread throughout the army of the Peninsular, and is often credited with the success of Wellington’s army there and at Waterloo. It was a system that created what one Colonel called ‘Pliable Solidarity’ whereby Wellington’s army could manoeuvre ‘as smoothly and as rapidly as we could have done on Southsea Common.’

Moore’s legacy didn’t end with Waterloo. His system changed the way in which soldiers were trained in the British Army, as did his belief that it was only by bringing out the best in men that they would become the best of soldiers.

References

Sir John Moore’s System of Training, Colonel J.F.C. Fuller, D.S.O., 1924, Hutchinson & Co, London

Images

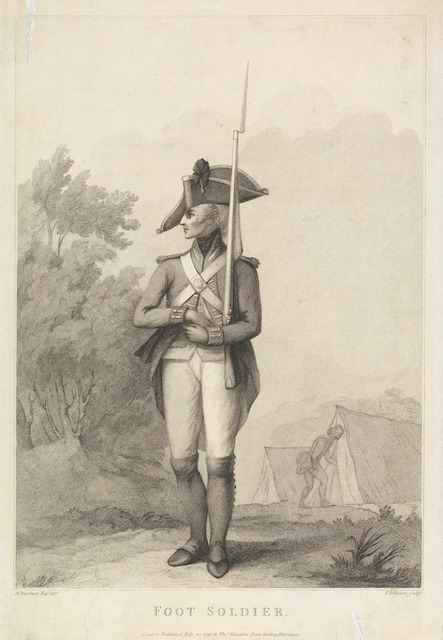

Foot Soldier

Francis David Soiron, Born 1764, after Henry William Bunbury, 1750–1811, British, Foot Soldier, c. 1791, Stipple engraving, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.11150

Soldier’s Head

George Dance RA, 1741–1825, British, Soldier’s Head: front and back, undated, Watercolor on medium, slightly textured, cream laid paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B2001.2.771

A review on Epsom Downs

John Nixon, ca. 1760–1818, British, A Review on Epson Downs, undated, Watercolor and graphite with pen and black ink on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.6237

British Riflemen

British Riflemen by G Hamilton Smith (1776-1859) & aquatinted by I.C. Stadler, depicting 5/60th & 95th Regiments. source Wikimedia

Soldiers Drilling

A Picturesque Representation of the Naval, Military and Miscellaneous Costumes of Great Britain, 1807, London, John Augustus*Atkinson, James Walker

The 28th Regiment at Quatre Bras

1875 by Elizabeth Thompson National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne

Purchased, 1884

Rifleman at musketry practice

John Augustus Atkinson, 1775–1831, British, A Rifleman at Musketry Practice, undated, Pen and black ink, Pen and brown ink and watercolor on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1975.4.18

Close order Drill and Advanced guard of a Battalion

Images taken from Sir John Moore’s System of Training, Colonel J.F.C. Fuller, D.S.O., 1924, Hutchinson & Co, London