In researching for the latest story in my Gentlemen Series, I’ve been looking at life in the British Royal Navy of the period. I have to say, a lot of it made grim reading.

If women had a hard time with lack of independence, and limited means of making a living during the early 1800s, men had a tough deal too.

I am, of course, talking about everyday-folk, not the wealthy sort from the landed and aristocratic classes — although many second sons from the well-to-do classes did join the navy, and therefore also shared to an extent, all the horrors and depredations of life on a ship.

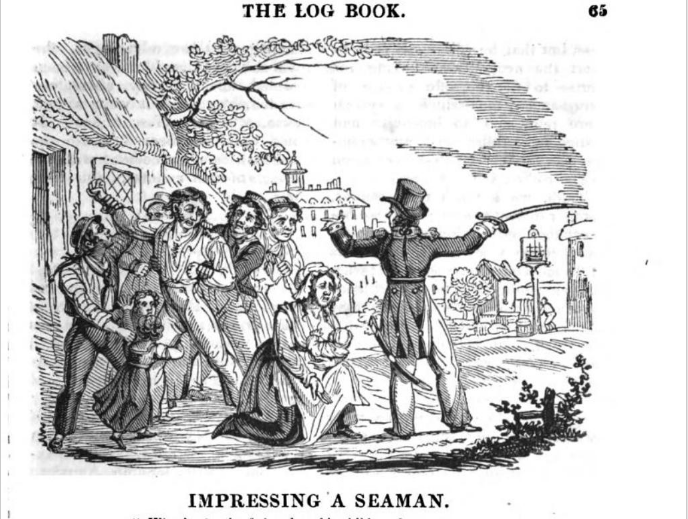

For a start, many crewmen on ships were ‘impressed’. By that, I mean that they were legally kidnapped and forced to work on the ships.

Impressment, carried out by press gangs, could take place both on land and at sea. There were two types of press gang – one was formed from a ship’s crew, and employed specifically to find men for that ship. The second type were permanent shore-based gangs, under the control of regulating captains. By 1795 there were 85 gangs operating in Britain, each with its own district. A team would be set up in a district, usually near to a seaport. The aim was to persuade already experienced seamen to join up, failing that, they would be impressed. If insufficient numbers of experienced seamen were found, then ‘landsmen’ — men with no sea-going experience, would be taken.

A headquarters or ‘rendezvous’ would be set up, usually in a local tavern, to which the volunteers and pressed men would be brought and held until they were transferred to ships. Many of those who were pressed decided to say they had volunteered, because volunteers received payment of a bounty for doing so. The head of a press gang was also rewarded with £1 for every man taken.

Impressment also took place at sea. Boats would be sent out to incoming merchant ships, and their crews mustered so that the most promising crewmen could be taken. For some crewmen taken in this way, it could be years before they saw their families again. In fact it could be years before a crewman set foot on land at all, as so great was the fear that they would desert, shore leave was rarely granted.

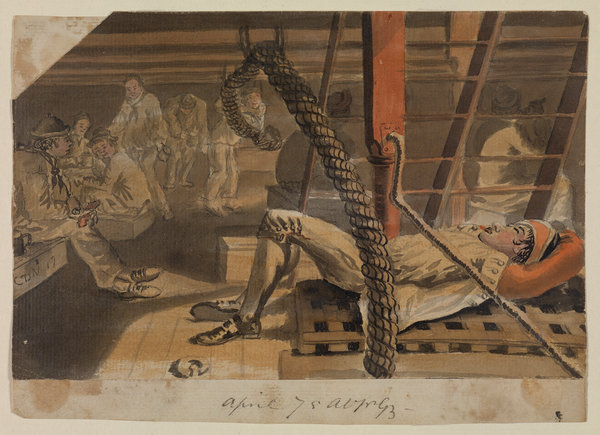

Once on board a ship, for those new to seafaring, it would be a strange environment. The day was divided into ‘watches’, a division of time lasting four hours, except for the ‘dog watches’ which were two hours. The first watch started at 8pm and ended at midnight. The start of this watch also marked the time of ‘lights out’, when those coming off duty went to sleep. Next, was the middle watch from midnight to 4am, then the morning watch from 4am to 8am. The forenoon watch was 8am to midday, then the afternoon watch from noon until 4pm. The dog watches were 4pm to 6pm, and 6pm to 8pm, when the whole cycle started again.

The crew would usually be divided into two teams, called larboard and starboard. Each team covered one watch, at the end of which they would be replaced by the other team, who took the next watch. This ensured that throughout the day, a sufficient number of men were manning the ship at all times. Some ships operated a three team system, but this was not usual.

Each four hour watch was divided into eight equal periods, signalled by a number of strikes on the ship’s bell. The ringing of eight bells meant that the watch was ended. Two sandglasses were used to calculate the time, one half-hour glass to signify each ringing of the bell, and a four hour glass to indicate when the watch was completed.

The day began when those who were not already on watch were woken up by the sounds of ‘All hands ahoy’, followed by ‘All hammocks ahoy’. This usually took place around six bells (seven o’clock in the morning). The men were expected to dress themselves, and take down their hammocks, which would then be rolled and carried up to the deck, where they would be stowed for the day in netting around the sides of the ship. In poor weather they were kept below decks.

In the place where they slept, each man had his own allocated space to hang his hammock, and because space was limited, it was usual for these spaces to be alternated between men of different watches. This meant that when one watch was on duty, those sleeping had double the official allowance of 14 inches width per man.

What about sanitary arrangements? For officers who had their own cabins, there were ‘seats of ease’, such as those in Admiral Nelson’s cabin on Victory, concealed in the quarter galleries. For other officers with cabins, chamber pots would be used, which were emptied over the side.

On larger ships-of-the-line, there were two ‘round houses’ on the bulkhead of the upper deck, which were reserved for warrant officers; after 1801, one of these was reserved for the sole use of men in the sick berth.

The rest of the crew had to make do with seats placed over trunking drained into the sea. These were located in a structure behind the figurehead, and were known as the ‘heads’. Other ships also had ‘piss dales’ on their sides, these were basin-like receptacles with pipes draining out to the sea.

Despite these facilities, poor though they were, some crewmen still resorted to relieving themselves over the gratings to the hold, a problem that caused the Admiralty to issue instructions that sentries should be posted by the gratings to stop this occurring.

Overall, it would appear that conditions on a ship, while cramped, were arranged in such a way as to make life for the crew as sanitary and as comfortable as possible. In some ways, conditions on a ship might have been an improvement for some men compared to what they had at home.

Join me again soon, when I will be looking at other aspects of life on board ship.

References

The Wooden World, by Rodger, N.A.M, Collins, 1986

News of Nelson, John Lapenotiere’s Race From Trafalgar to London, Allen, Derek and Hore, Peter, SEFF édition, 2005

Nelson’s Navy, by Lavery, Brian, Conway Maritime Pess, 1989

Jack Tar: Life in Nelson’s Navy, Adkins, Lesley and Adkins, Roy, Abacus, 2011

One Response