Last week I had the privilege of taking a tour of the Bodleian Library’s conservation workshop. Housed in the impressive Weston Library, the workshop is on the top floor, where it is able to take full advantage of the unobstructed light coming in from the windows ranged across one side of the room.

The Bodleian Conservation workshop

On first entering, one could be forgiven for thinking not much is going on. Technicians, heads bent, work at their desks and benches; there is no amazing gadgetry on view. No, a great deal of the magic is rather understated, relying on some very basic and quite old techniques, but magic nonetheless.

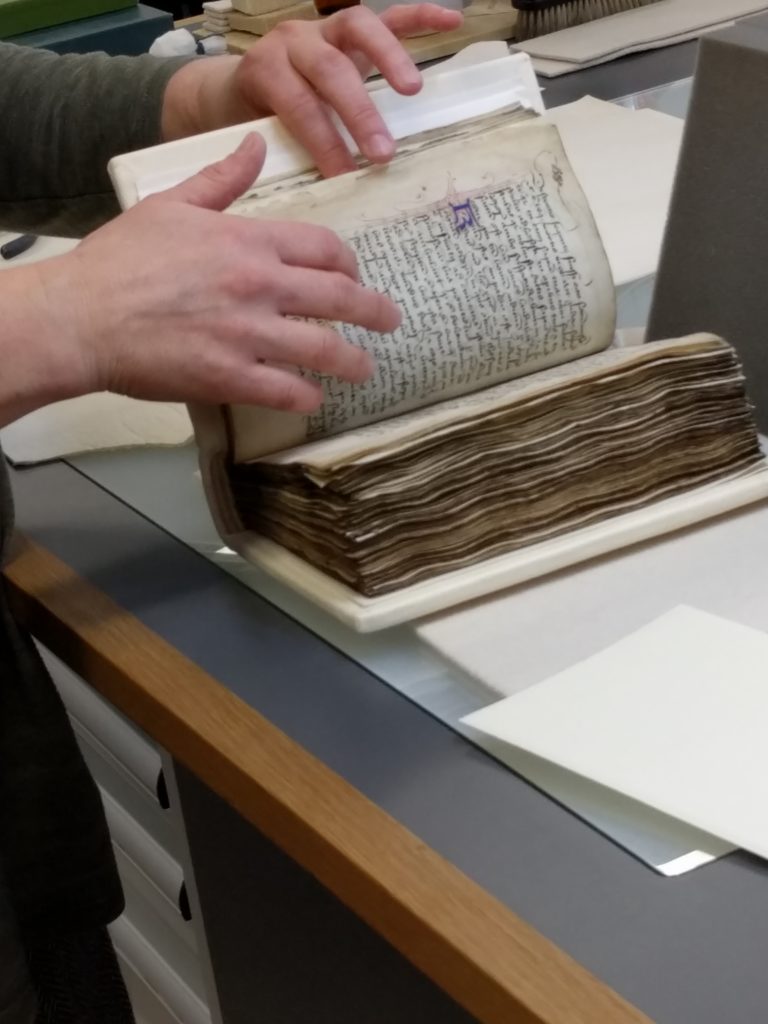

My first stop was at a workbench where a medieval manuscript, in a very poor state when it was acquired by the Library, was looking something like it might have done when it was first created. The pages, which had been swollen and distorted due to water damage, now resembled something much more ‘book-like’; the new boards, made of oak and hand stitched, were covered in beautiful white tawed leather. I learned that tawing leather is one of the oldest processes of treating prepared hide or skin with aluminium salts and (usually) other materials, such as egg yolk, flour, salt, etc. Tawed leather differs from tanned leather, used mainly for shoes, etc, in that the end product is pliable and durable, but not water resistant.

A medieval manuscript with new boards and tawed leather cover

It was wonderful to see the craftsmanship that had gone into restoring something so old into something of beauty again, strong enough to withstand further (careful) handling by academic researchers in the Library’s reading rooms.

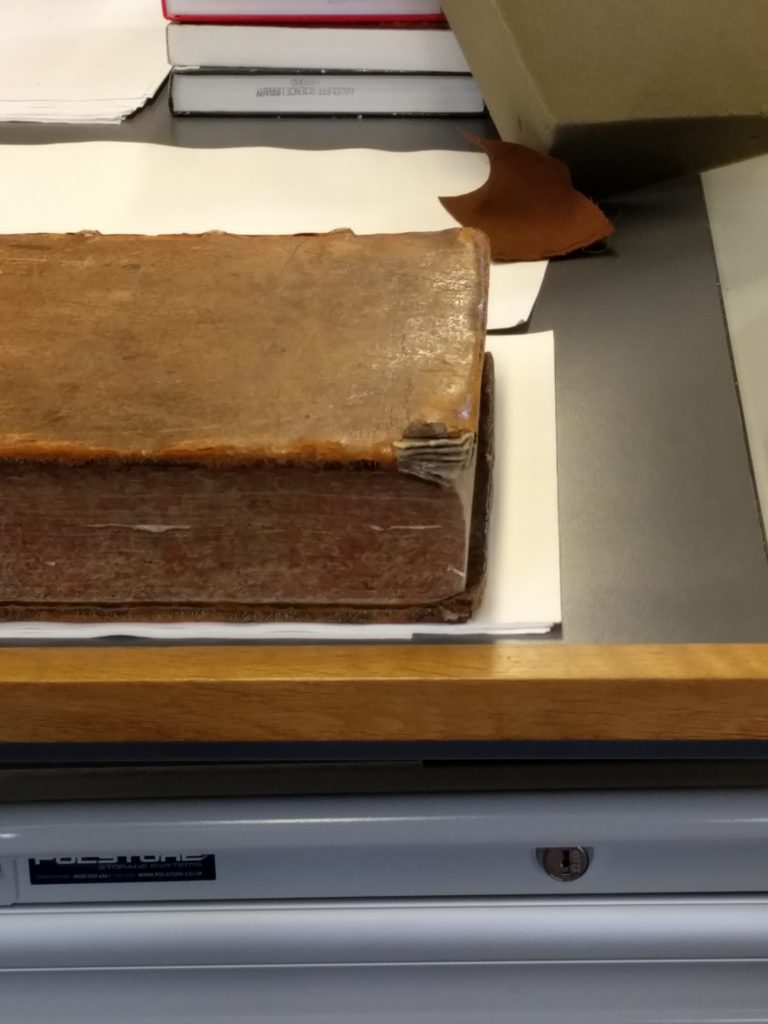

A volume in for repair

My next stop was at a workstation dealing with more modern objects – posters created in the 1930’s. They had been stored folded and the resultant creases had cracked and the posters were in danger of completely falling apart. By the use of tiny pieces of tissue-like material, each poster was being repaired and strengthened, to be eventually stored flat in individual archival quality polyester envelopes. Archival polyester is a transparent, colourless, inert plastic; the objects inside can then be safely examined without direct contact being made.

The highlight of my tour was seeing the famous Selden Map of China (MS. Selden Supra 105). This marvellous object, one of the first Chinese maps to reach Europe, arrived at the Bodleian in 1659 from the estate of a London lawyer, John Selden. Its true importance was unrecognised for many years until 2008 when American scholar Robert Batchelor examined it and discovered two features that distinguished it from all other Chinese maps of the period.

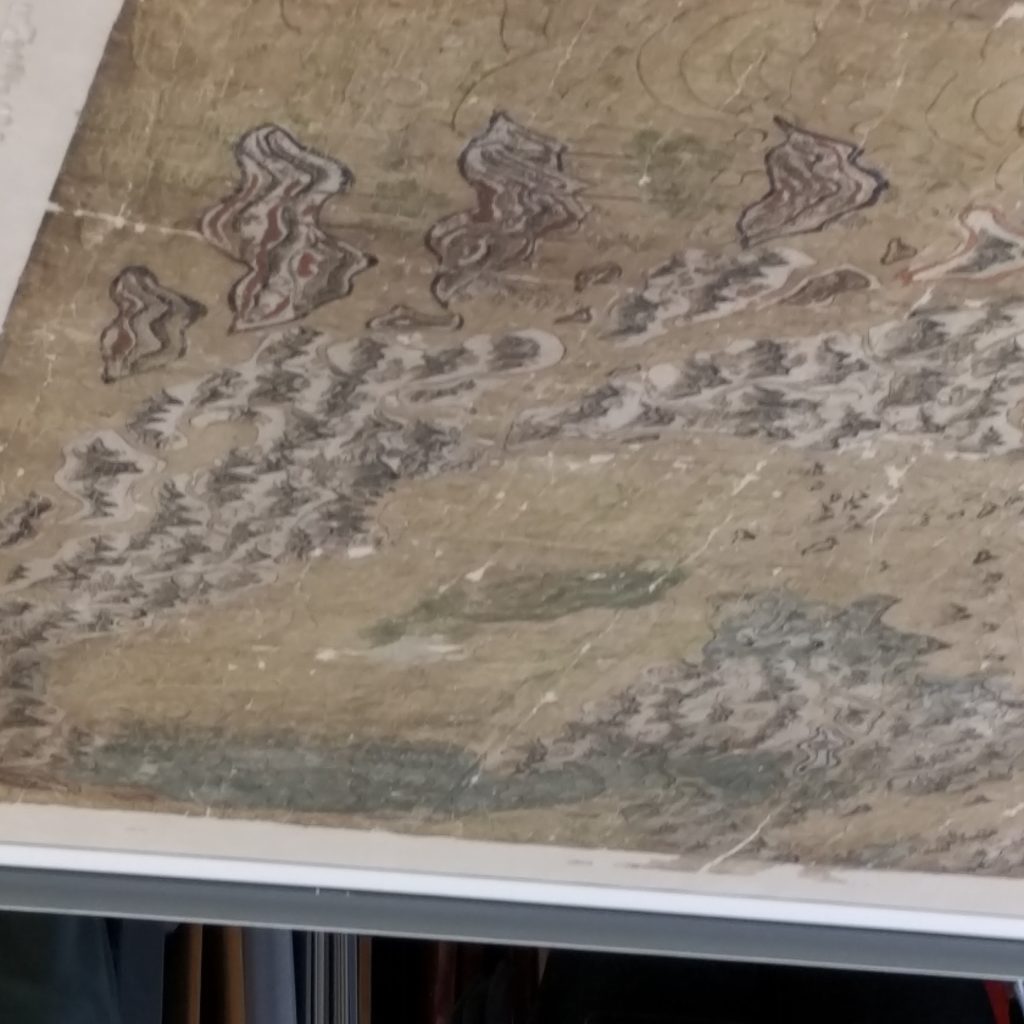

A section of the Selden Map of China

First, it did not just depict China, but the whole of East and Southeast Asia too. Earlier, and indeed many later maps of China, show China as the centre of the known world, with China taking up almost the whole of each map. By contrast, the centre of this map is the South China Sea.

The second feature identified by Batchelor was the presence of shipping routes. The Selden Map of China charted the commercial world as no map, whether European or Chinese, had done before. It importantly indicated the extent of China’s connections with the outside world at a time when that country was generally supposed to have been isolated.

A shot of the map giving some idea of its size

Another important feature of the map only became apparent during the course of its conservation. Removing the old backing, it was found that the main sea routes were also depicted on the reverse, indicating that it was a first draft. The routes were drawn using systemic geometric techniques, utilising voyage data obtained from a magnetic compass and distances calculated from the number of watches, a technique with no western equivalent.

It was fascinating to listen to the curator who undertook most of the conservation, explain the painstaking techniques involved in the process. Much research was required before any work on the map commenced, including visits to the Far East to establish the type of materials and dyes available to the original creator of the map. Knowledge of this type is important to ensure that new materials used in the conservation process will not cause an adverse reaction. I was astonished to discover that one of the adhesives used is derived from seaweed.

Some of the tools used in the conservation process; note the seaweed in the jar.

As you might be able to see from my photograph, the map is stored flat in a specially constructed conservation box. Unfortunately, because of the limitations of my phone camera and my lack of skills as a photographer, I am unable to show you the details, including the exquisitely tiny Chinese script that adorn the map. Hopefully the map will feature in one of the Bodleian’s future exhibitions and you will be able to see them for yourself.

The final stop on my tour was a look at a beautifully illuminated oriental manuscript undergoing examination by an electronic scanner with something very like a microscope attached. Images invisible to the naked eye could be seen on the computer monitor and the state of the paint and pigments assessed. I’ve examined manuscripts in the past using a magnifying glass, which can bring up a lot of detail, but this was truly amazing.

My tour was an eye opener in more ways than one. As someone who has worked with manuscripts for many years, I’d always appreciated the work that had gone into enabling me to handle them, but without actually understanding the techniques involved. This visit changed all that. What I found most interesting was the blend of old and new techniques required to conserve these wonderful objects, but what I found most awe-inspiring was the dedication and painstaking skills of the curators and technicians who deal with them, allowing scholars to examine them and discover more about our past.

My sincere thanks go to the Friends of the Bodleian, Virginia M Lladó-Buisán, Head of Conservation and Collection Care, and her staff, for organising this tour.