My previous blog post covered only some aspects of life in the Royal Navy at the time of the Napoleonic Wars, so I thought I’d write a bit more about other aspects of life.

Being pressed into the navy, didn’t mean one worked for nothing — all members of the crew were paid. From 1797, the lowest paid were the landsmen (those with no previous sea experience) at a rate of £1 1s 6d per month, rising to £1 2s 6d in 1807. Able seamen were paid £1 9s 6d, rising to £1 13s 6d in 1807. A midshipman was paid according to the type of ship he served on, anything between £1 15s 6d and £2 10s 6d — by 1807 they were earning between £2 0s 6d and £2 15s 6d. Lieutenants received £7 per month, plus expenses if they employed a servant. In 1807 this had risen to £8 8s, or £9 2s, if they served on a flagship.

However, the men didn’t receive their pay on a regular basis. It was the custom that no-one received any pay until they had been in service over six months; even then, a seaman would not receive the full amount due when the next pay day came, but just the balance due to him for any period served over and above his first six months. Payment for the first six month’s service was retained until the ship was paid off.

When seamen were transferred from one ship about to enter port, to another just about to sail, it was usual for them not only to be refused shore leave, but also for their pay to be witheld. This was a source of much annoyance and anger, and also meant the men were forced to borrow, usually from the purser, who exploited their need by charging high prices.

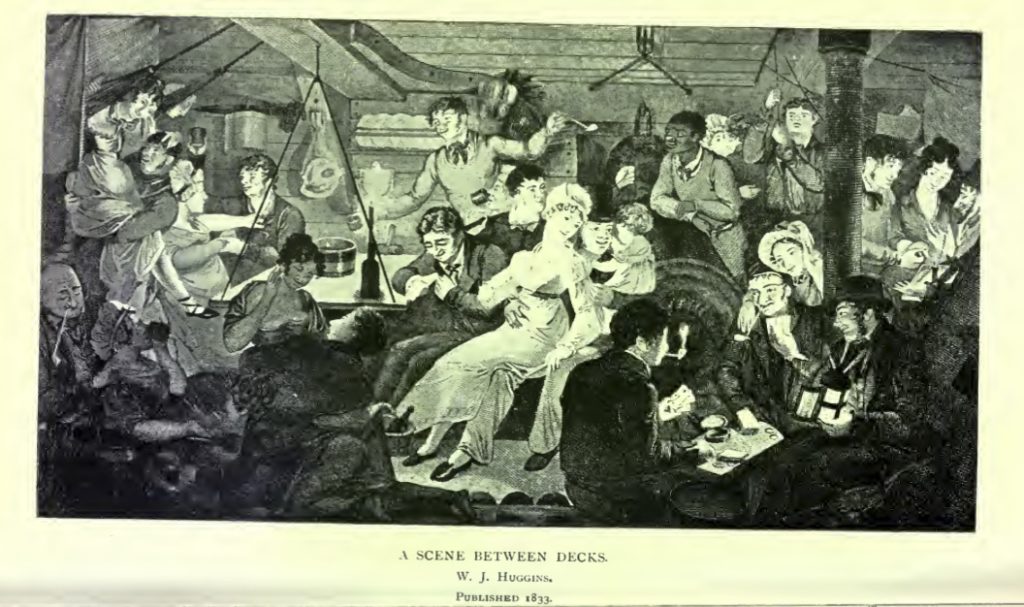

When a ship was in a home port, the ship’s company would be paid, and even if they were not allowed shore leave, there were ways that a crewman could spend his cash. Bum-boats would come alongside, and traders, usually women, would take orders and payment up front for goods such as fresh meat, bread, butter, tea, coffee, and other luxuries. Needless to say, alcohol was another commodity also supplied.

A seaman could also arrange for a portion of his pay to be sent to his family. This money would be deducted at source and collected by his dependents from a pre-arranged location. For families who didn’t have this arrangement, their only option was to try and meet the ship their man was serving on when it came into port. For some, this could mean a long, difficult, and expensive journey, and there was no guarantee that the ship would be in port by the time they arrived. These problems were encountered not only by the wives of crewmen, but also officer’s wives.

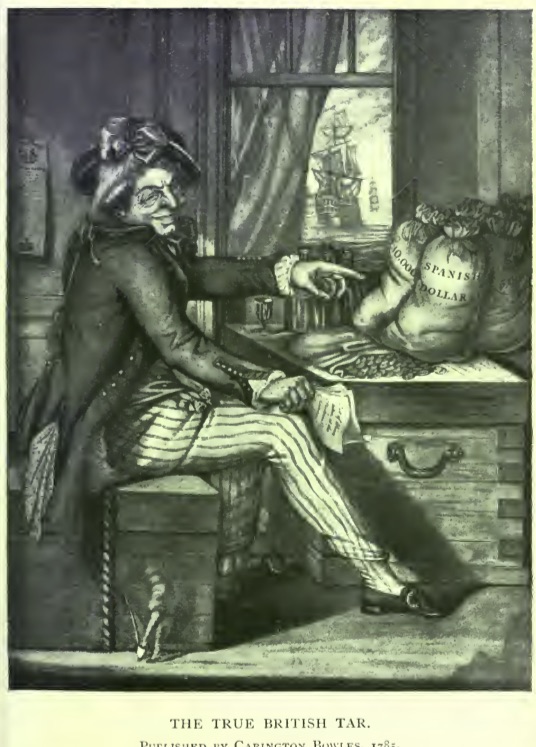

In addition to their pay, seamen were also, if they were lucky, entitled to prize money. A captured enemy vessel and its cargo, was classed as a ‘prize’; its monetary value was calculated and paid to the crew involved in its capture, according to a fixed scale of shares. In exceptional cases, prize money could be more than a seaman could expect to earn in his lifetime.

When a crewman’s career at sea was over, he ceased to be paid. However, for officers it was different. Lieutenants and all ranks above were entitled to half-pay when they were not on active duty; some also received pensions. Even when not employed, post captains and higher ranks were promoted automatically, when those in higher ranks died off.

One of the benefits of serving in the navy was that one could at least guarantee being fed. All those at sea were given the same rations, though officers were able to supplement these by buying better food. A seaman’s diet consisted of hard sea biscuit, fresh meat, if the ship was in or near port, or otherwise salted meat, pea soup, and burgoo (oatmeal). In addition, each seaman had an allowance of beer, butter, sugar, dried pease, and cheese. If a ship called into a port, fresh commodities would be purchased as a welcome substitute for some of the above dried or preserved foodstuffs.

Ships that were on patrol in the North Sea, and therefore able to frequently return to the home port of Yarmouth for re-provisioning, enjoyed greater quantities of fresh food than the crews of ships on more distant voyages. Amazingly, ships employed to blockade French ports as far down as the Basque Roads, were sometimes supplied with fresh food from bum-boats coming all the way from England, suggesting that the profit from these trips made the risk worthwhile to the bum-boats’ crews.

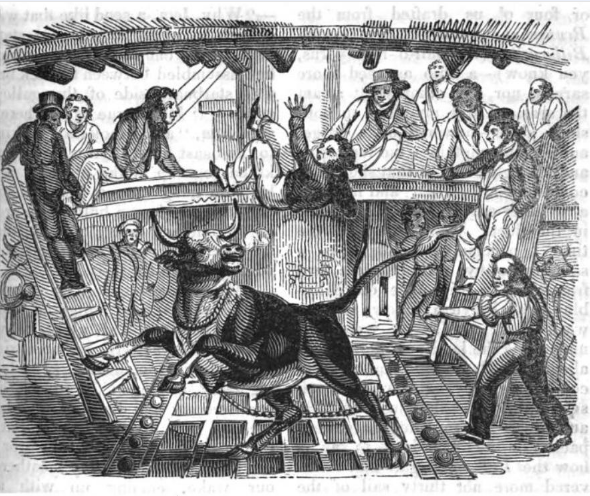

Live animals were also kept on board ship, not only for their meat, but also for milk and eggs. Most of these belonged to the officers, but it was known for crewmen to club together and purchase animals of their own. Unbelievably, fishing was only occasionally permitted, but when it was, it added another fresh element to a seaman’s diet.

Meals were eaten by the crewmen in their mess groups, usually at tables set between the guns. Officers would eat in the wardroom, while midshipmen had their meals in the gun room. The captain and his guests, if any, dined in his cabin.

Join me soon for another insight into life at sea with Nelson’s navy.

References

The Wooden World, by Rodger, N.A.M, Collins, 1986

News of Nelson, John Lapenotiere’s Race From Trafalgar to London, Allen, Derek and Hore, Peter, SEFF édition, 2005

Nelson’s Navy, by Lavery, Brian, Conway Maritime Pess, 1989

Jack Tar: Life in Nelson’s Navy, Adkins, Lesley and Adkins, Roy, Abacus, 2011

The British Tar in Fact and Fiction, Robinson, C.N., Harper and Bros, 1909

I had no idea that live animals used to be kept on ships. that’s fascinating!

Yes, it was pretty much news to me too, Lydia. According to reports, at the start of a voyage, a ship could resemble a farmyard, with animal noises and smells.