Gabrielle, the heroine of my forthcoming Regency novel, An Adventurer’s Contract, is a French émigrée living in London. The inspiration for her story was an article that appeared in the February edition of The Monthly Magazine for 1810. You can read my post about it here. The article set me thinking about what life must have been like for those aristocrats who had escaped revolutionary France and settled in England.

Before the storming of the Bastille on 14th July 1789, many of the wealthier French classes had already departed for England, but after this date the numbers seeking sanctuary shot up. The process of moving abroad wasn’t straightforward. Passports not only were expensive, but there was the added risk of being thought a traitor simply by applying for one.

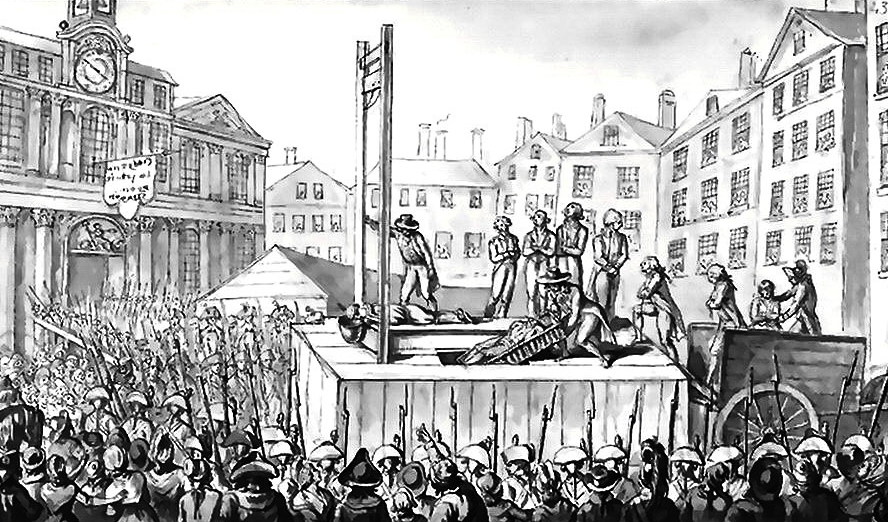

Their possessions had been confiscated by the French authorities, and from April 1793 a law was passed that any émigrés returning to France would be condemned to death, to be guillotined within twenty-four hours of their arrest. Effectively, once they had fled, they were trapped. Therefore, émigrés were only able to flee with what they could carry, so they arrived on English shores usually with few funds to support themselves after spending money on their transport there. To add to their troubles, many of them had no experience of earning a living.

Even those French aristocrats who had English relatives were not always welcomed by them. Some in the British political classes were suspicious of the newcomers, recalling French support for America in overthrowing the yoke of British rule and worried that the contagion of revolution was being imported.

Fortunately, not everyone in England were hostile to the French incomers. Local people in the coastal towns where the émigrés first arrived, supplied food, clothes and accommodation.

Lord Sheffield, hearing of a French vessel that had been wrecked near Newhaven sent his Swiss servant to help and to escort the survivors to his home.

‘Madame de Balbany, sister to Madame de Sesmaisons, with her three children, from three to eight years old, as fine brats as ever were seen, their parish priest and man and maid.’

Others were not so lucky. One French lady arriving in Dover on a snowy January afternoon with her children, one only thirteen days old, was unable to find any shelter until gone midnight.

Meanwhile in London, John Eardley Wilmot (1750-1815), the Member of Parliament for Coventry, was so concerned that large numbers of émigrés were at risk of starvation that he called for a meeting at the Freemason’s Tavern in Bloomsbury in September 1792 ‘to take into consideration some means of affording relief to their Christian brethren.’

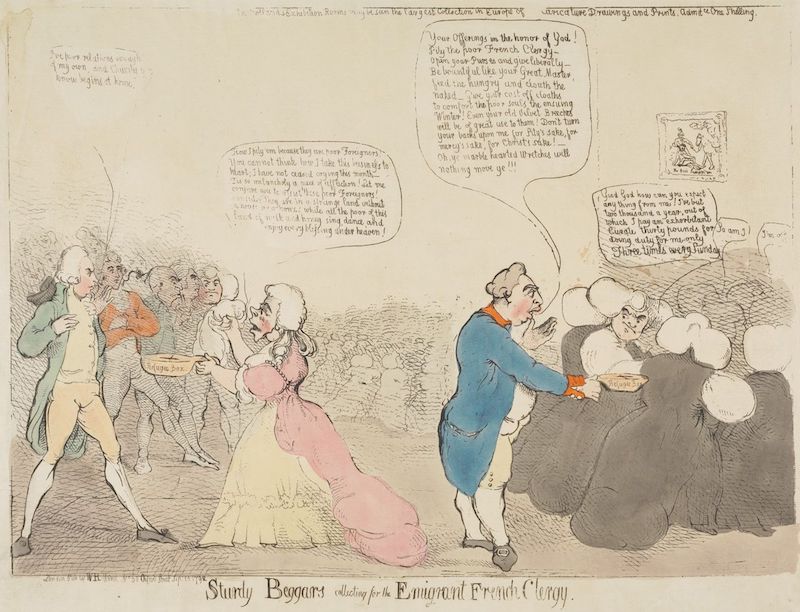

The meeting was attended by notable figures, including the Duke of Portland, the Marquis of Buckingham, and the Bishops of London and Durham, and a fund was set up for ‘The Relief of the Suffering Clergy of France in the British Dominions.’ This was the foundation of what became known as the Wilmot Committee.

However, it soon became clear that not only the clergy required financial assistance; many lay people were also in dire need. Another committee was therefore set up to give financial aid to émigrés who were not members of the clergy. In February 1794, the Prime Minister, William Pitt allocated public funds to the Committee of one thousand pounds per month.

An allowance of £1. 11/- 6d was paid per month to each man under sixteen years of age and over fifty years of age.

Women and girls over 14 years received the same amount, while children under fourteen years of age received £1. 2/- per month.

Men who were under the age of fifty with a wife who was ill, or with dependent children received an extra ten shillings and sixpence.

The most needy were also granted £2. 2/- towards clothes.

The Government allocation to the fund was increased to three thousand pounds per month in March 1795.

It has been estimated that between twelve to fifteen thousand French émigrés received financial assistance from the government.

In return for this financial help, all men between the ages of sixteen and fifty years who were not fathers were required to have a medical exam and, if passed fit, were enlisted in the army. Young girls were also expected to seek work.

In 1795 a special committee under the patronage of the Duchess of York was set up to specifically help female émigrées. ‘Heartsick as we were at the sight of these scenes of distress in which so many persons of the same sex and rank as ourselves have been so innocently involved…’ English aristocratic ladies in London and several other cities raised money so that items such as clothing, linens, and medicines could be provided for these impoverished French females.

Of course, living on charity was neither desirable or viable longterm, so many French upper class émigrés were forced to find ways of earning a living. Some became language teachers or taught dancing, fencing, and chess; others opened schools, restaurants, or became tailors.

French women also discovered ways to make a living. Needlework, once considered an acceptable female accomplishment now became a talent used to earn an income. French ladies who designed and made dresses found a ready market for their wares. Madame de Saisseval made straw hats then turned her hand to embroidering the white linen dresses which were fashionable at that time. Painting was another skill whereby French ladies were able to earn money.

The Comtesse de Guéry discovered a talent for making ices; the Prince of Wales and the Royal Dukes were known to patronise her café, where her ices were considered to be the best in London. Other aristocratic ladies turned to writing, producing memoirs and novels.

The suspicion that spies could be lurking in the émigré community, ready to foment revolution and anarchy was unsurprising; the last thing the government wanted was for the ideas of republicanism to spread. To tackle this the Aliens Act of 1793 was passed. It empowered the Home Office to collect information about foreigners, tracking their movements and imposing restrictions. By placing restrictions on all foreigners, it was thought that the government would be able to distinguish “the real emigrant and object of generous compassion from the plotting incendiary.”

Émigrés were forced to live within fifty miles of Cornhill and ten miles from ports or the coast. Their lodgings could be inspected without warning for firearms. The fear of an invasion and the possible presence of spies ready to assist Napoleon was very real at this time.

Which leads neatly on to my story…

My heroine Gabrielle, is a little better-off than many of her compatriots. She has some money on which she is able to live. But being kind-hearted, she likes to help others and uses her embroidery skills to raise funds for impoverished French families. However, despite leading a quiet life, Gabrielle is drawn into a murky world of spying, suspicion, and treachery. Who is spreading rumours about her and can she escape the looming threat of the noose?

If you enjoy historical romance, I’ve written a series of Regency stories; you can discover them here.

I’ve also written contemporary romance stories with lots of mystery… and a few ghosts.

All my books are available on Amazon and Kindleunlimited.

References

Margery Weiner, The French Exiles 1789-1815, John Murray, London, 1960

Kirsty Carpenter, ‘British Government Aid to French Émigrés and Early Humanitarian Relief during the French Revolution’, Historical Reflections, Volume 48, Issue 3, Winter 2022, pp.51-68

Muller HW. The Wilmot Committee: Redefining Relief and National Interest in Britain during the French Revolution. Journal of British Studies. 2022;61(2):343-372. doi:10.1017/jbr.2021.172

Juliette Reboul, French Emigration to Great Britain in Response to the French Revolution, War, Culture and Society 1750-1850, Palgrave Macmillan, 2017

Images

John Eardley Wilmot (1750-1815) by William Daniell, after George Dance soft-ground etching, published 1 June 1811 (3 August 1802) National Portrait Gallery, Ref: NPG D12162

Unknown artist, Sturdy Beggars Collecting for the Emigrant French Clergy, 1792, Etching, hand-colored, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1981.25.1671.

Execution of nine émigrés in October 1793 By Unknown author – book La Guillotine en 1793 by H. Fleischmann (1908), Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=11471992