I’m sure many people today believe that women in the past didn’t do much outside of the domestic sphere. Up to fairly recently it was almost a given that a woman’s place was in the home. Women have been called the weaker sex. We often hear how it took World War I to change things. According to some, it was only when their menfolk were called away to the trenches that women rolled up their sleeves and undertook what had previously been considered men’s work.

Some of this may be true, but it is not the whole picture. You might be surprised by the occupations women have held in the past. For hundreds of years women have been leaving the domestic arena, earning a living for themselves, and even leading adventurous lives. Are they really the weaker sex?

Prior to the 20th Century

When Britain was an agricultural nation it wasn’t only the men who worked on the land. Before men became the dominant force in medicine many women worked as midwives. Brewing was also something that women did to earn a living. In fact, up to the 1500s brewing was solely a female occupation. With the industrial revolution of the 19th century women entered the factory workforce alongside men.

Women down the Mines

In the past it was not unusual to find the weaker sex working down mines. Women worked the same shifts as men, often at the coalface, but for half the pay. Women were employed down mines until the Mines and Collieries Act of 1842 finally made it illegal for boys under the age of ten years and all women and girls to work underground. It was not the hard work that destroyed women’s health that caused this turnaround, but the scandalous fact that women were working topless next to naked men.

Indeed, in many spheres of work employers preferred female workers because they commanded lower wages.

Women have been active in all sorts of occupations not usually associated with females, but too often their contribution has been disregarded… making them invisible and supporting the myth that they are the weaker sex. Yet, very often women shared the same hardships and challenges imposed on their menfolk.

Women in the Navy

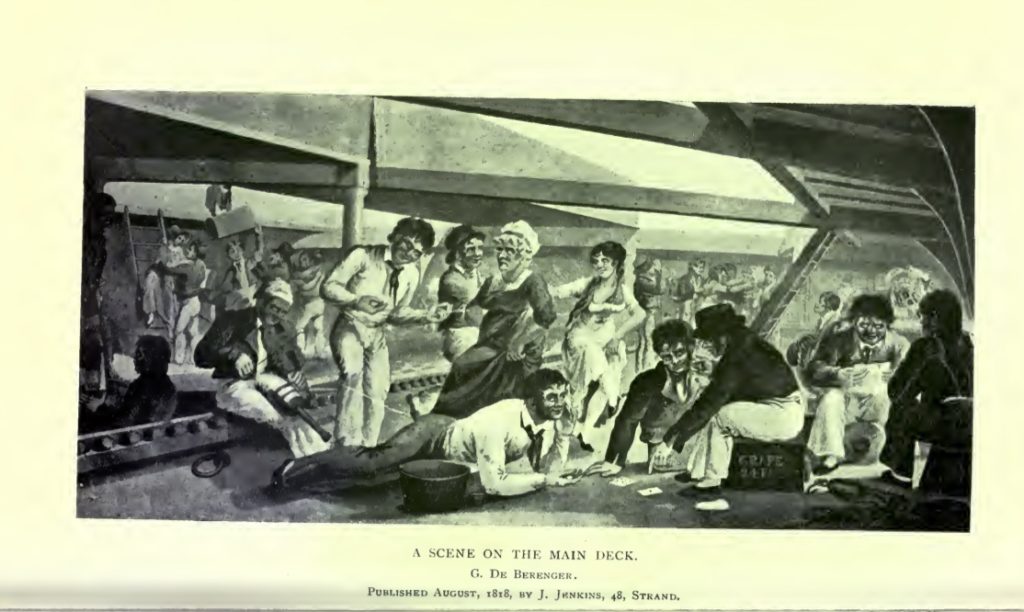

The Royal Navy is one example of a profession that we do not associate with the ‘weaker sex’. However, although not part of the service themselves, women were often to be found on board ships. Contrary to what was once believed, these women were not all prostitutes. They were the spouses of captains, masters, or warrant officers. In certain circumstances crewmen’s wives were also permitted on board. During sea battles these women were expected to play their part by assisting the surgeon in caring for the wounded.

Women even gave birth on ships. The mother of Mary Campbell gave birth to her daughter during the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801 and the little girl spent her early years on navy ships. Imagine how diffficult it must have been to not only cope with life at sea but also to bring up a young family.

Life on board ship was dangerous for everyone. In 1812, during action between a British ship and two French vessels, a wife who had been assisting the surgeon was told that her husband had been fatally wounded. When she went to tend to him she too was killed by a French shot. Although the husband’s death was recorded in the ship’s log there was no mention of his wife. We only know of her existence and untimely death because of an article published in the Annual Register by one of the ship’s officers.

In addition to helping the surgeon, women undertook more dangerous tasks such as acting as powder monkeys during battle – carrying gunpowder cartridges from the magazine up to guns. There is evidence that, on occasion, women even manned the guns.

Compelling evidence of this female contribution can be found in official documents. Explaining why he was refusing to award a medal to a woman, Sir Thomas Byam Martin wrote:

‘She is fully entitled to a medal. Upon further consideration this cannot be allowed. There were many women in the fleet equally useful, and it will leave the Army exposed to innumerable applications of the same nature.’

Women in the Army

Army life also had its share of female participants – wives who followed their husbands when they went to war. For a long time, soldiers were discouraged from marrying and in 1685 it was even made an offence for a soldier to marry without permission. At home, facilities for soldiers’ wives and families were non-existent, they were forced to share the common barrack room. The first official married quarters were only built in 1860.

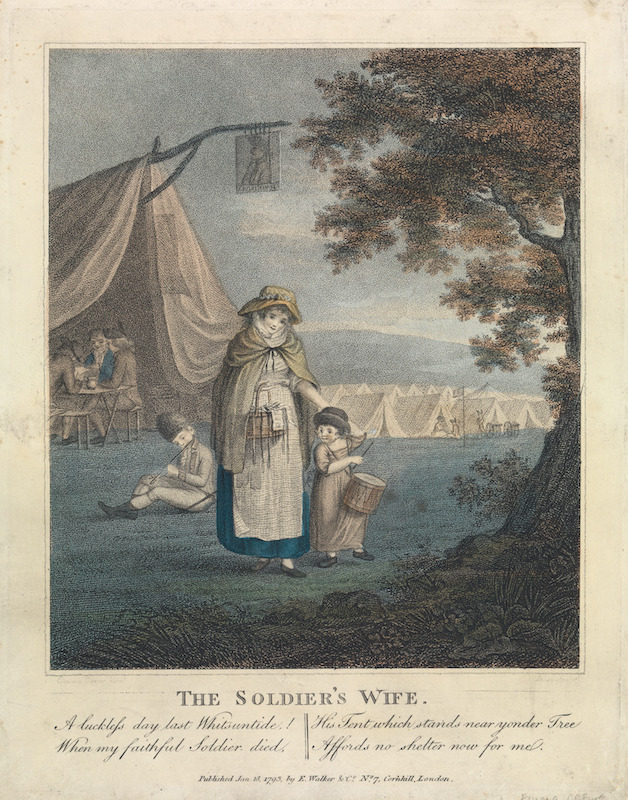

When their husbands were posted abroad not every wife was allowed to accompany her husband. There were quotas for those who could go, with lots being drawn to decide. Despite knowing of the hardships ahead, many women were determined to stay at their husbands’ sides. Subject to almost the same levels of discipline as the men, while bringing up a family, undertaking the myriad ‘domestic’ tasks, not to mention the danger of facing enemy action, the life of a soldier’s wife was not for the fainthearted.

Lady Smith

One of the most well-known of soldier’s wives was Juana María de los Dolores de León Smith, Lady Smith (1798 –1872) the wife of General Sir Harry Smith, who fought under Wellington in the Peninsular Wars and at Waterloo. They met after the Storming of Badajos in 1812 when Juana was only fourteen years old and Harry was twenty-five. Within a couple of weeks they married with Wellington’s approval. Harry’s own words tell of Juana’s life as an army wife:

‘She has shared with me the dangers and privations, the hardships and fatigues, of a restless life of war in every quarter of the globe.’

Going from secluded convent life to one where she was exposed to all the dangers and hardships associated with an army at war, Juana met the challenge. It wasn’t long before she became a much respected and loved figure to her husband’s men and fellow officers, even gaining Wellington’s admiration for her stoical nature and positive disposition.

I hope these examples have shown that women’s lives weren’t always confined to the home and hearth. Join me soon when I examine the lives of three more ladies who didn’t stay at home and give the lie to the notion of the ‘weaker sex’.

References

Jack Tar: Life in Nelson’s Navy by Roy and Lesley Adkins, 2008, Little Brown

The Wooden World: An Anatomy of the Georgian Navy by N.A.M. Rodger, 1986, Collins

Redcoat: The British Soldier in the Age of Horse and Musket by Richard Holmes, 2001, Harper Collins

Following the Drum: The Lives of Army Wives and Daughters, Past and Present by Annabel Venning, 2005, Headline

The Autobiography of Lieutenant-General Sir Harry Smith BART., G.C.B. edited with the addition of some supplementary chapters by G. C. MOORE SMITH, M.A., 1903, John Murray (available online: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/57094/57094-h/57094-h.htm#Page_61

Images

Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, Soldiers on a March: “To pack up her tatters and follow the Drum”, recto, 1811, Hand-colored etching, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1975.3.111.

Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, Harvesters Resting in a Corn Field, recto, between 1805 and 1810, Watercolor, pen and black ink, pen and red ink, and graphite on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1986.29.469.

(Hot Cross Bun Seller) Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, Set of eight (6): Cries of London, recto, 1799, Etching with aquatint, colored by hand, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1985.36.1422.

Juana Smith, at the age of 17, painted by an unknown artist 1815 in Paris

English Barracks:

Thomas Malton, 1726–1801, British, And Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, after Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, English Barracks, 1791, Hand colored etching and aquatint on thick, slighlty textutred, beige, wove paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1978.43.301

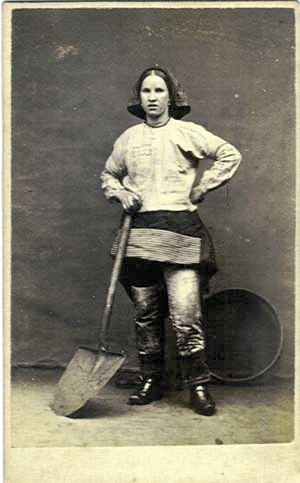

Wigan pit brow lass, photo Wikipedia

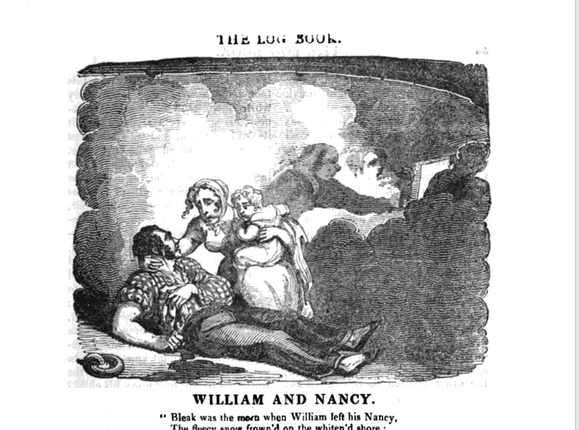

A seaman’s wife in the midst of battle, from The Log Book, or Nautical Miscellany, 1830

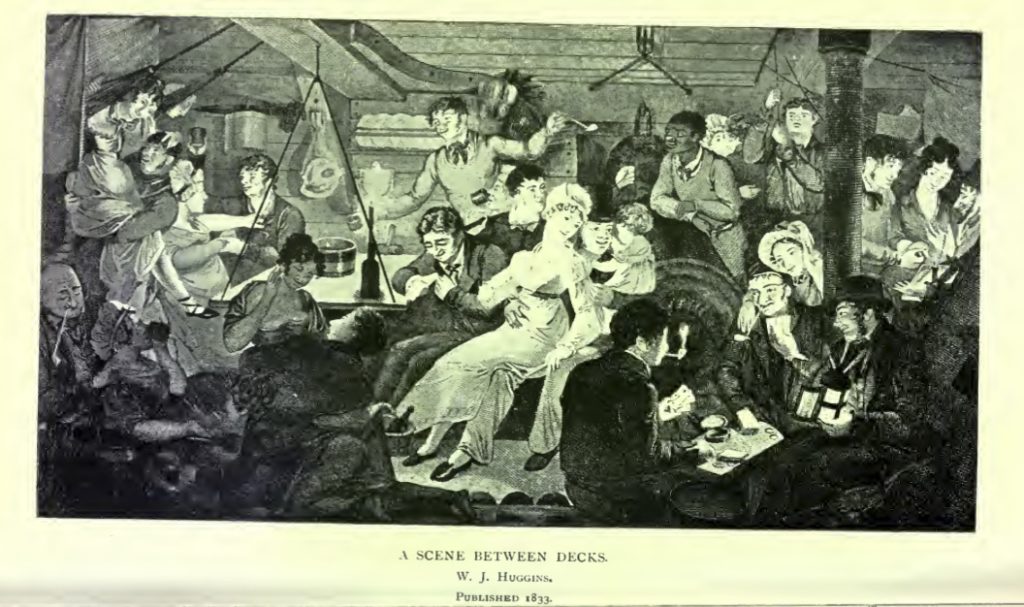

A Scene Between Decks

The Soldier’s Wife

William S. Leney, 1769–1831, British, after Emma Crew, active 1783, British, The Soldier’s Wife, 1793, Colored stipple engraving, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1978.43.215