It’s been a while since I posted, so apologies if you’ve been waiting for the final instalment of my trip to Bath.

On the recommendation of a friend, the final full day of my trip included a visit to St Swithin’s Church in Walcot. I’d not been there before, but because it has Austen connections, it was a place I thought I should see.

After breakfast, husband and I headed off from our hotel into the bustling centre of Bath and walked up Milsom Street. This broad thoroughfare is lined with shops, and I think Jane Austen – who mentions it in both Persuasion and Northanger Abbey – would not be too surprised to discover that it is still a lively hub of the city. Pierce Egan’s Walks Through Bath (1819), describes it as ‘the very magnet of Bath’ and apparently, it was the place to be seen:

‘The beaux in Milsom-Street, who sought renown,

By walking up, in order to walk down!’

Part way up Milsom Street, at number 43, and sadly obscured by scaffolding at the time of our visit, (photo above is not mine, and pre-scaffolding) is the ghost of a sign advertising the Circulating Library and Reading Room. From what I can discover, this sign was probably painted for Frederick Joseph, who owned a bookshop and circulating library at this address in 1822.

Turning right at the top of Milsom Street, we headed towards the Paragon, a street of beautiful listed Georgian houses, designed by Thomas Warr Attwood (c1733-1775) a builder, architect, and local politician. It too, has connections with the Austen family, as Jane’s uncle, Mr Leigh Perrot on his frequent visits to Bath stayed at No 1, Paragon, and it is likely that Jane herself stayed there on her first recorded visit to Bath in 1797.

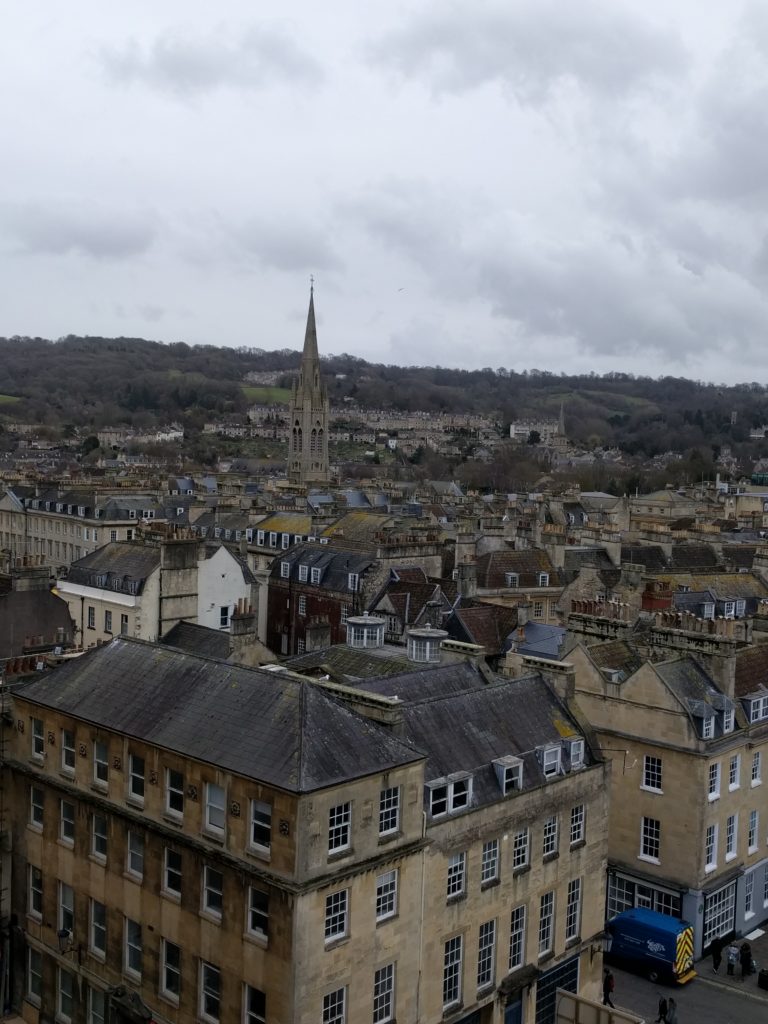

A short distance later, we arrived at St Swithin’s – surprisingly the only remaining Georgian church in Bath, and built between 1777 and 1790 by architect John Palmer (c1738-1817). The view of the church from the Paragon is pretty uninspiring, and one does not get a sense of the size or the elegance of the building. Walk further on however, until you reach the junction with Walcot Street, and this impression changes.

Egan mentions that the parish was thought to contain 20,000 souls ‘and its returns to Government are greater than any parish in England, excepting that of Mary-le-bone’. This would seem to indicate not only that St Swithin’s had a high number of parishioners, but also that they tended to be the wealthier sort. Jane Austen’s parents were married at St Swithin’s on 26 April 1764, and her father George Austen is buried there. Other notable people connected to St Swithin’s are William Wilberforce, the abolitionist, who was married here on 30 May 1797, and the author Fanny Burney, who was buried here in 1840.

The inside of the church is a wonderful example of the clean lines and elegant space characteristic of Georgian architecture. The morning light floods in through the two tiers of windows lining both sides of the main church, and a broad balcony wraps round three sides. Another arresting feature is the great number of marble monuments and memorials lining the walls. According to the church’s own website there are 163 monuments in total (I didn’t count them), dedicated to members of the middle classes – army and navy officers, like Rear Admiral Sir Edward Berry, who fought alongside Nelson at Trafalgar, noted portrait painter, William Hoare RA, and leading surgeon at the Mineral Water Hospital, Jerry Pierce FRS. Quite some time was spent walking round the church and reading these memorials, before we ascended the stairs to take in the view from the balcony.

Finally we descended into the crypt. We were advised by a very nice lady who spoke to us about the church, that until recently, this had been quite a forbidding and ‘creepy’ (her words) space, but thanks to some recent renovations, it is now a much more welcoming place. We went down using the stairs, but there is a lift for those who need one. Here we found airy rooms with white painted walls, toilet facilities, and a lovely cafe. Needless to say, I couldn’t resist a slice of tasty homemade cake to go with my coffee.

Outside there is a graveyard, and an article from the Bath Journal of February 1755 states:

Wednesday last a Black Girl (servant to a Gentleman in the Square) was buried at Walcot Church: -There were six Black Men to support the Pall; and several others, of the same Complexion, attended the Corps, as Mourners.’ I think this is an interesting insight into the diverse ethnicity that has always been a feature of life in England, and which for so long has been hidden and often denied.

Leaving the churchyard, we continued along the London Road until we came to the Walcot Methodist Chapel, which Egan describes as being ‘one of the most elegant chapels in Bath’. I certainly wouldn’t dispute that. The foundation stone was laid on March 1815 and the chapel opened in May 1816.

According to Egan again, the chapel is ‘71 feet in length, and in width 52’. More worryingly, he goes on to say it ‘has a commodious school underneath it, capable for instructing 800 children, with an excellent enclosed burying-ground.’ The mind boggles! Unfortunately, the chapel was not open at the time of our visit, so I was unable to ascertain whether the space inside really was commodious enough for 800 children.

Returning towards St Swithin’s, we turned left to head back into Bath via Walcot Road. Along this street you will find lots of quirky independent shops, galleries, and cafes, and on Fridays and Saturdays this street hosts an Antique and Flea Market. Alas, it was mid-week when I was there this year, so no market — however, I have been lucky to visit on the right day on previous visits and can highly recommend it for anyone looking for an unusual souvenir of their visit to this wonderful city.

Well, that’s it for now. I hope you have found my posts about Bath interesting, and that they have whetted your appetite for making your own trip. Do let me know if you have any favourite places in Bath that you think I might have missed — not that I need an excuse to go back!

Refs:

- Pierce Egan, Walks Through Bath (1819)

- http://paintedsignsandmosaics.blogspot.com/2010/07/circulating-library-and-reading-rooms.html.

- R.A.L. Smith, p.93, Bath (1948) B.T. Batsford Ltd

- Trevor Fawcett, Voices of Eighteenth-Century Bath (1995), Ruton, Bath

- John Haddon, Bath (1973) B.T. Batsford Ltd