This post first appeared on the English Historical Fiction Authors blogspot

I expect most people will have heard of the Elgin Marbles and the controversy surrounding them. The focus of their story has always been Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin and 11th Earl of Kincardine, and whether he acquired the marbles illegally. But what is known of his first wife Mary, who accompanied him on his travels? Like most women of the time, her life has been overshadowed by her husband’s, and her main claim to fame has been her involvement in a scandalous divorce case. However, closer inspection of the records reveals a woman of lively intellect who possessed great strength in adversity.

Mary was born in April 1778, the only child and heiress of William Hamilton Nisbet of Dirleton and Belhaven, and his wife, Mary Manners, granddaughter of John Manners, 2nd Duke of Rutland. William Nisbet was a wealthy Scottish landowner, who during Mary’s teen years became a Member of Parliament, thereby introducing Mary to London society. As a wealthy heiress, related to nobility, and by all accounts very attractive, Mary was quite a catch.

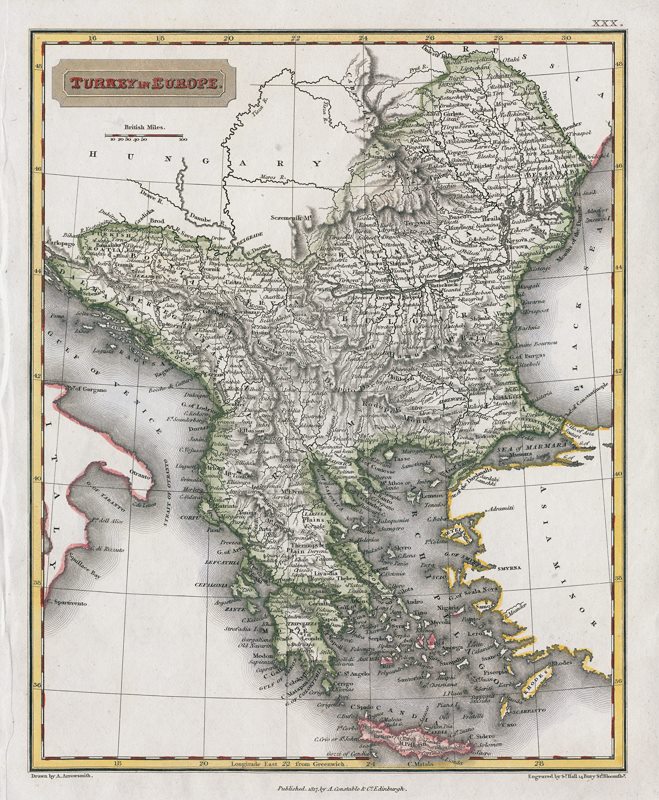

Thomas Bruce, although titled and well-connected, was somewhat less wealthy. A second son, he had inherited his title just before his fifth birthday, his older brother having died at the age of seven years. Educated at Harrow and Westminster, he attended St Andrews University and also studied in Paris, giving him an excellent command of the French language. He joined the army, but saw no active service, and he commenced his diplomatic career in 1790, when he was posted to Austria. After various other postings, in 1798 he was appointed Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire. Shortly before departing to take up this position he courted and married Mary.

They married in March 1799, and the couple departed Portsmouth for Constantinople in September the same year, with Mary knowing she was pregnant. This seems to have been a particularly brave decision on her part. Not only were they travelling at a time when Britain was at war with France, but she was heading to a relatively unknown and alien part of the world. To go when she was also expecting her first child, a time when many women can feel vulnerable and apprehensive, takes a certain sort of courage and determination.

As mentioned previously, Mary was wealthy, and upon their marriage Thomas Bruce would have had access to her wealth. This was used to ensure that the Elgin household was one befitting a British Ambassador. Their party consisted of not only artists – Elgin tried unsuccessfully to engage the twenty-four year old J.M.W. Turner to accompany him – but also a private secretary, musicians, and a chaplain. Apparently, it was specified that at least one of the musicians should be able to teach the pianoforte, presumably to Mary, so it appears that they did not travel lightly.

It took them two months to get to Constantinople, by way of Lisbon, Gibraltar, Sicily, and several other ports of call. Once in Constantinople, they based themselves in the recently vacated French Embassy, which Mary renovated. As the Ambassador’s wife she proceeded to establish herself as a society hostess, hosting balls and parties. For a young woman – she was only twenty-one – pregnant, and living in an unfamiliar environment, she seems to have been remarkably cool-headed.

But not everything went smoothly. Despite their wealth, they were subject to the same health hazards affecting ordinary people. A letter of July 1801 from Reverend Hunt, the family chaplain, to their private secretary, mentions that Lord Bruce, Mary’s fifteen month old firstborn son, was recovering from fever and dysentery, which must have been a worrying time for Mary.

After a successful sojourn as a society hostess in Constantinople, in 1802 Mary set off on her travels again, this time accompanying her husband to Athens. She now had another child, Mary, in addition to her firstborn, Lord Bruce. In lively letters to her mother, Mrs Hamilton Nisbet, Mary makes light of the perils of travel. She describes how, after they departed Constantinople on 28th March 1802, their ship was caught up in a storm, so bad that ‘Bruce was almost the only person on board who was neither sick nor frightened’.

By 1st April, still suffering from rough weather, Mary insisted on going ashore in the Bay of Mandria (Porto Mandri, in the south-east of Attica), where they pitched a tent in a cave and stayed overnight. For some reason the children had been left aboard ship, a situation that was remedied the next day, when they too were brought ashore.

Bad weather was not the only danger, pirates were an ever-present threat. It was then decided that the remainder of the journey be undertaken overland. Horses and asses were hired, and accompanied by two wet-nurses, and a washerwoman, the journey continued. Mary, in the same letter, describes the next six hours as ‘most tedious’, which rather sounds like an understatement. Arriving finally at a village for the night she says ‘I expected to sleep like a Queen! But in this Alas! I was disappointed’. Her humour and ability to make light of what must have been very trying circumstances are what make her such an engaging personality. She goes on to describe how they spent ‘a most delightful night’ plagued by fleas that kept her and the children awake.

With Athens another nine hours journey away, Mary paints a wonderful picture of her children, riding in baskets attached to the mules, ‘we deposited our little treasures in the baskets and off we set’. She admits her own exhaustion, ‘I really thought of getting off my horse and laying down, for I was never so faged’ (sic). Arriving in Athens at about nine in the evening, the children however ‘arrived as fresh and lively as possible’. They at least must have enjoyed some comfort and rest on the journey.

By the 15th April, Mary had obviously recovered sufficiently from the journey to visit the Bath, which she describes ‘it very far surpassed my expectation’ although, ‘the dancing was too indecent beyond anything’.

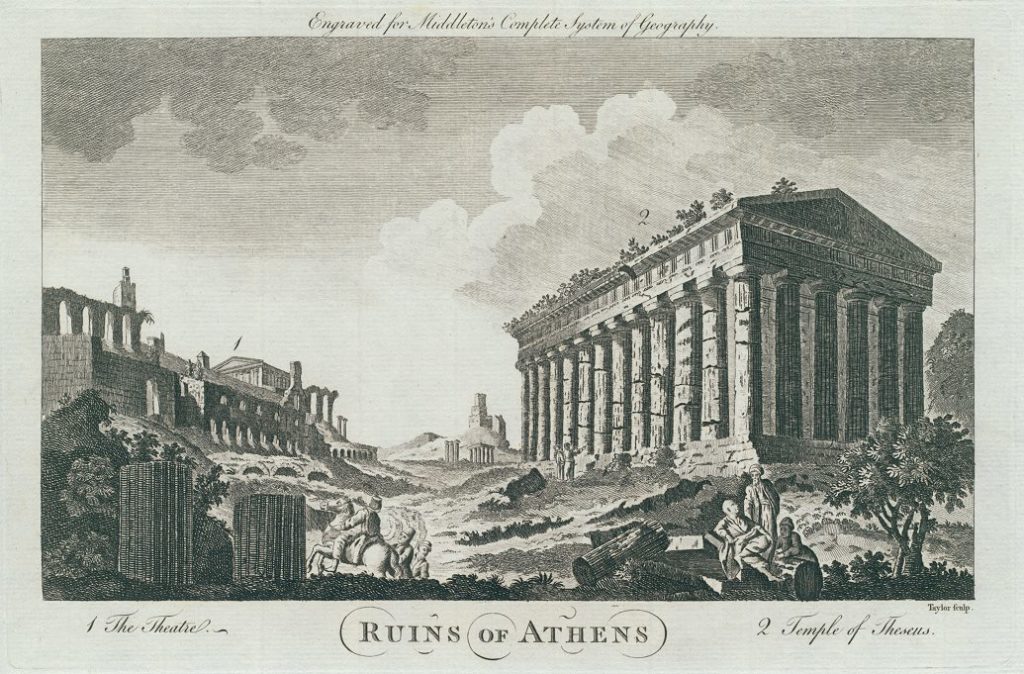

Life in Athens must have been quite pleasant for Mary; she mentions giving a ball and spending her days at her pianoforte, reading, or arranging medals in the gallery. She dines at two and drives out every afternoon in her curricle. Just like any modern mother, the safety of her children was also of paramount concern – she arranges for a gate to be put at the top of the stairs, so that the young Lord Bruce has a safe place to toddle about.

But Mary had itchy feet; in another letter to her mother she describes leaving the children in Athens on 3rd May while she accompanies her husband on yet another tour. Embarking on a ten-oared barge, they departed at noon on a very hot day, taking in a stop to visit ruins on the way to Port Nisea, where they stayed the night in a miserable cottage.

The next day their travels continued by barge to Port Cencha, where they stayed in the Governor’s house. Mary describes a visit to the ladies of the harem, who had left their own house in the country in order to see her. An independent female who travelled with her husband and endured harsh conditions, must have seemed a novelty to the confined and restricted Turkish ladies. She writes that she was ‘deluged with rose water’ during her visit and treated as an honoured guest during the twenty minutes she stayed with them.

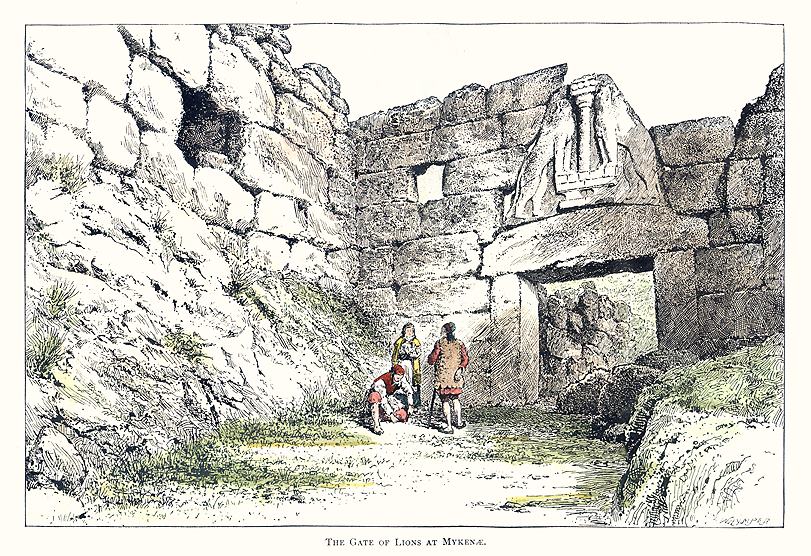

From Corinth, the party then travelled to Nemea and then onwards to the ruined city of Mycenae. Mary takes part in all the excursions to see the ruins, giving a lively account of how she had to crawl on all fours to enter one cavern, before creeping through another subterranean passage to the next vault. She mentions with some pride that a young man in their party, who had been instructed by his mother not to undertake anything that Lady Elgin herself did not undertake, refused to follow her into the second vault. Mary is not the faint-hearted female that we are led to believe is typical of the period in which she lived.

Having reached Tripolitza on 9th May, where they were given a lavish welcome by the Pasha, they stayed only a few days before setting off on the return journey to Athens. They had been warned against travelling further because of the threats posed by bands of robbers. Using a different route, Mary conveys her love of travelling by her vivid descriptions of the countryside and explorations of yet more ruins of ancient sites.

‘Our ride from thence was along the Bed of a Torrent, between very steep Mountains and Crags, covered with Myrtles, Arbutus, Oleanders, Olives, Locust Trees, Brooms, and other extremely beautiful Shrubs which grow there with the utmost luxuriance. I should certainly have been ruined could Money have bribed the Shrubs to have left the scorching Sun of Greece for the cooling breezes of the Firth. It undoubtedly was without any exception the most perfectly inchanting ride I ever took, quite in my style; the road very dangerous and the Mountains perpendicular.’

The ride took eleven hours and although Mary admits to being ‘fatigued’ one gets the distinct impression from her account that she loved every moment of it. They arrived back in Athens on 15th May. Throughout her various travels, the sleeping in caves, damp tents, or verminous cottages, Mary never complains, but describes everything with a positive tone and a sense of humour.

Another letter of Mary’s, this time to her husband, demonstrates what a loving and affectionate relationship they enjoyed. Her pet name is apparently ‘Dot’, though she refers to him always as Elgin. Here she boasts about how she persuaded Captain Hoste to take several cases of marbles aboard his ship. ‘How I have faged to get this done, do you love me better for it, Elgin? …I am now satisfied of what I always thought; which is how much more Women can do if they set about it, than Men.’

With such evidence of a strong, indomitable character, it is a wonder that she has been relegated to the footnotes of history and only famed for her acrimonious divorce. Further excursions are taken before the journey back to Constantinople; there are hair-raising accounts of encounters with pirates, storms, and treks along mountainous roads with precipitous drops to one side; all these are recounted in letters to her mother and read like an adventure story. Amongst it all, Mary still found time to attend a ball given by the Russian Consul when they stopped en-route at Tenos. Most surprisingly of all, it is learned from a letter of Elgin’s dated 8th October 1802, that Mary had in fact been pregnant during all these adventures. She gave birth to another daughter in late September of that year.

In January 1803, the Elgins left Constantinople by sea for Athens and thence to Malta; by April they had reached Rome, where they spent Holy Week. They travelled onwards via Genoa and Marseilles, and by great misfortune were in Paris when the First Consul (Bonaparte) declared all Englishmen in France between the ages of eighteen and sixty prisoners of war. Elgin was held captive in France from 1803 until 1806 and Mary worked hard to secure his release.

However, it was during this time that the marriage fell apart. There is some dispute as to Elgin’s affliction. What is not in dispute is that he lost his nose, a terrible disfigurement. Depending on which version you prefer, he was either suffering from syphilis or the mercury, which he was allegedly taking for a lung condition, caused his nose to disintegrate. Either way, Mary no longer wished to have intimate relations with him. The arrival on the scene of one Robert Ferguson of Raith complicated matters; he and Mary fell in love and, after much bitterness and an acrimonious divorce, Mary married Ferguson in 1808. The couple never had children of their own. Like many other women of her period, Mary faded from public view.

If you enjoy historical romance, I’ve written a series of Regency stories. I’ve also written contemporary romance stories with lots of mystery… and a few ghosts.

All my books are available on Amazon and Kindleunlimited.

You can discover them here.

Sources:

Wood, Gillen D’Arcy. “Mourning the Marbles: The Strange Case of Lord Elgin’s Nose.” The Wordsworth Circle, vol. 29, no. 3, 1998, pp. 171–177. JSTOR, JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/24043819.

Hunt, Philip and Smith, A. H. “Lord Elgin and His Collection”, The Journal of Hellenic Studies, Vol. 36, (1916), pp. 163-372. Publ. by The Society for the Promotion of Hellenic Studies. url: https://www.jstor.org/stable/625773?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

Vrettos, Theodore. The Elgin Affair: The Abduction of Antiquity’s Greatest Treasures and the Passions It Aroused. Secker & Warburg, London, 1997

Mitsi E. “Commodifying Antiquity in Mary Nisbet’s Journey to the Ottoman Empire”. Travel, Discovery, Transformation. 2014;1:45.

Portrait of Mary Nisbet, Countess of Elgin (1777 – 1855) by Francois-Pascal-Simon Gerard (1770-1837) Scottish National Gallery accession number: NG 1496 Scottish National Gallery(On Display) https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/4957/mary-nisbet-countess-elgin-1777-1855