My previous post about Sir John Moore’s system of training officers and soldiers at his training camp at Shorncliffe in Kent concerned some of the practicalities of of life, such as dress, cleanliness, and discipline. But Sir John believed that every aspect of a soldier’s life should be regulated and that, with training and application, promotion to officer rank was possible for all. According to Moore, if a soldier was thoroughly trained and carried out his duties to the full there should be no bar to promotion.

To improve morale, Moore introduced two sorts of medals for meritorious behaviour and long service. Brass medals were reserved for those soldiers who discharged their duty with ‘peculiar ability and courage’. Silver medals were for individuals who performed a voluntary duty which benefited or brought honour to the regiment or brought about the ‘peculiar private happiness of some individual suffering under the calamity of a campaign’. A soldier awarded a silver medal was to be exempted from all duties except those not ‘connected with the more honourable ones of arms’. A record of the award was entered in the regiment’s Book of Merit.

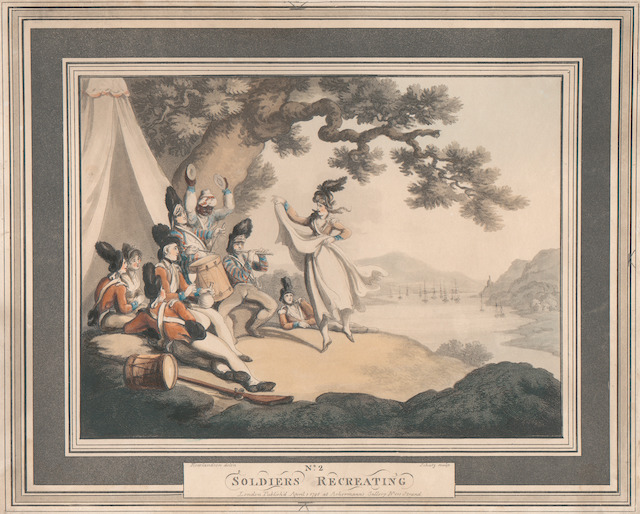

Exercise in the form of sports such as cricket, football, leap-frog, quoits, vaulting, and running, was encouraged to promote good health and camaraderie, ‘all manly and healthy exercises’. Dancing was also considered a good way to pass free time ‘it keeps up good humour and health’ and stopped the men from spending their free time in ale-houses, where all sorts of vices lurked.

All the men were expected to know how to swim. This had practical applications too, as those on campaign were often called on to cross rivers or embark and land from ships in not always ideal conditions.

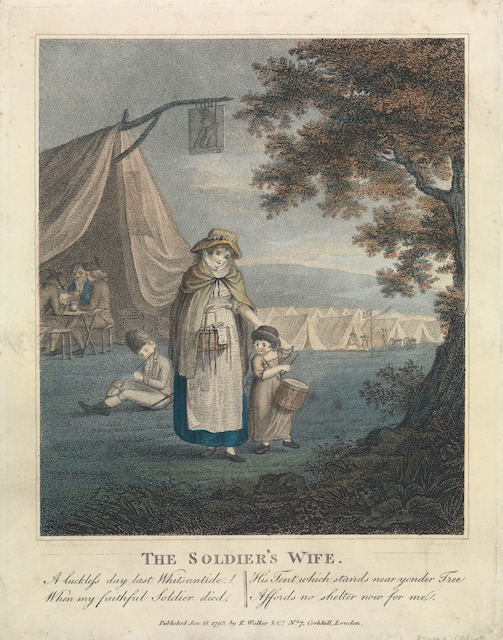

A soldier’s married life was also something that Moore did not ignore. Six married women for every hundred men were allowed to accompany the soldiers. They had to be of good character and have no more than two children.

Because these women were not supported financially by the army, all regimental needlework and washing was to be done by them, for which they were paid. Officers were instructed that their linen should only be given to the regiment’s women to wash and that it must be distributed equally amongst the wives. A laundress received 5d per week from the Quartermaster for washing the shirts and socks of the soldiers.

If a woman proved not to be of good character she was not permitted to stay with the army. However, women in this situation were not abandoned. Their friends and family would be contacted, or some provision made for them whereby they could earn a living. Failing that, a place in a poor-house was arranged for them. ‘They will not be turned adrift on the world, for such an act is ever to disgrace the Corps.’

Moore set up a Charity Fund in the Rifle Corps and much of this benefited the married women of the Corps. Whenever a soldier’s wife was ill or about to give birth, her husband could apply for financial assistance from the Charity Fund. The children of the regiment were also not neglected. Commanding officers were enjoined to consider them as much under their protection as the men and their wives, and to ensure that they were healthy, cleanly clothed, and attended school regularly.

Moore understood the importance of education. A regimental school was set up for ‘the instruction of those who wish to fit themselves for the situation of Non-commissioned officers’. Every sergeant had to be able to read and write and understand basic arithmetic. The school was open everyday except Sunday, and when it was not occupied by the men it was used to teach the children of the company.

Next time, I’ll finally be looking at the military drills that every soldier had to learn under Sir John Moore’s System of Training.

References

Sir John Moore’s System of Training, Colonel J.F.C. Fuller, D.S.O., 1924, Hutchinson & Co, London

Images

Soldiers on a March

Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, Soldiers on a March: “To pack up her tatters and follow the Drum”, 1811, Hand-colored etching, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1975.3.111

The Soldier’s Wife

William S. Leney, 1769–1831, British, after Emma Crew, active 1783, British, The Soldier’s Wife, 1793, Colored stipple engraving, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1978.43.215

Women hanging out washing

Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, Album Drawing, undated, Graphite and pen and ink on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B2001.2.1482(26)

An Officer and his Servant

Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, An Officer and his Servant, undated, Watercolor with pen and gray ink over graphite on medium, moderately textured, blued white laid paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.325

Soldiers recreating

Heinrich Joseph Schutz, active 1798, after Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, Soldiers Recreating, 1798, Aquatint, hand-colored, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.12985

Soldiers Embarking

Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, Soldiers Embarking, undated, Watercolor with pen and gray ink, over graphite on medium, moderately textured, cream, laid paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

This is so interesting, Penny. Just two children and paying the women to do their laundry was a brilliant idea. Wonderful.

Yes, the army in general didn’t make any financial allowances for the women and children who followed the army. I think they only received half the food rations of the men even though they were enduring the same conditions, so paying them was a bit of a breakthrough.