These last few weeks have mostly been spent on research for my next book.

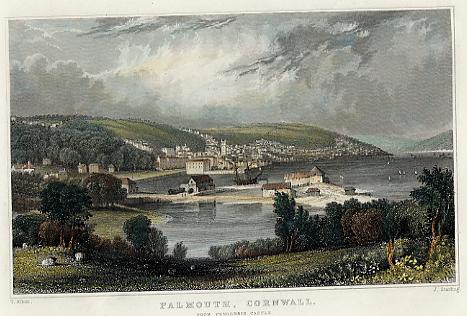

The main location I have in mind is Falmouth in Cornwall. For those of you who don’t know, Falmouth is a thriving seaside town near the western southernmost tip of England.

Falmouth didn’t really exist as a town until the 17th century, when local landowner Sir John Killigrew petitioned King James I for approval of his building plans. The town grew and Sir Peter Killigrew, a descendent of Sir John, built a Custom House there, obtained a patent from the then Commonwealth Government for a weekly market and two fairs, as well as a ferry from Falmouth to Flushing. Finally, on August 20th 1660, a Charter was granted by the newly restored Charles II for Falmouth to be incorporated as a borough. Falmouth was definitely on the up.

Conflict between the now Protestant England and Roman Catholic France in the 1680s meant that communications between Britain and the Iberian Peninsula and the Mediterranean became difficult, as land routes through France were closed. A solution had to be found. It was suggested that letters for these destinations should be sent by ship and that a regular service of these ‘pacquet boats’* be set up for this purpose.

Falmouth was chosen as the terminus for this service.

There were several excellent reasons for this, which together outweighed the inconvenience of Falmouth’s distance from London along poor roads.

It was sufficiently far away from the French coast to make the packet boats safe from attack by privateers.

It’s location meant it was a secure shelter from wind and weather.

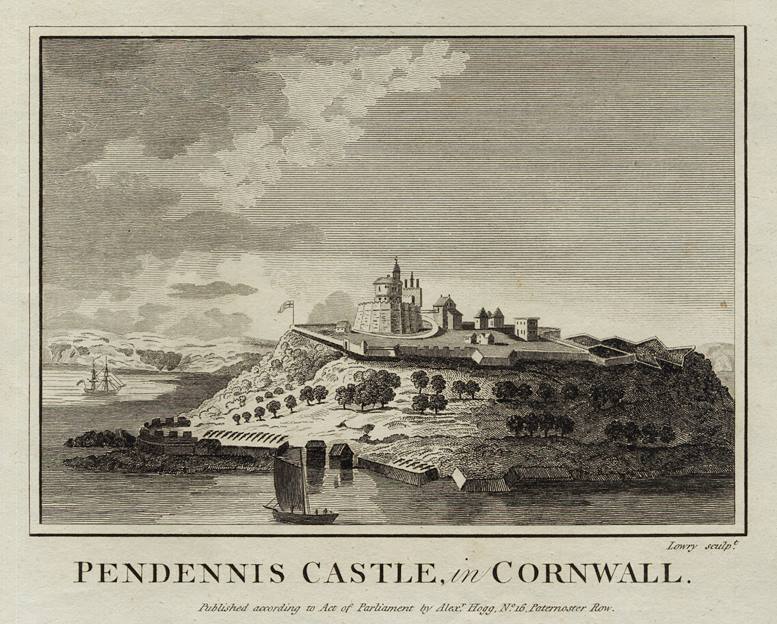

It’s entrance and waters were protected by the fortresses of Pendennis Castle and St Mawes, which would deter raids by enemy shipping.

With its deep estuary, there were numerous anchorages.

One of the first packet services was between Falmouth and the Groyne of Corunna, with the first two ships named Spanish Allyance and Spanish Expedition. By the 1830s, there were forty vessels sailing to Lisbon, Gibraltar, Malta, Corfu, Bermuda, Leeward Islands, Windward Islands, Mexico, Rio de Janeiro, and Buenos Aires.

From 1775 to 1815 Falmouth became quite a fashionable place thanks to the numerous passengers who stayed there, either on their way to, or returning from the many places that the packet boats called at.

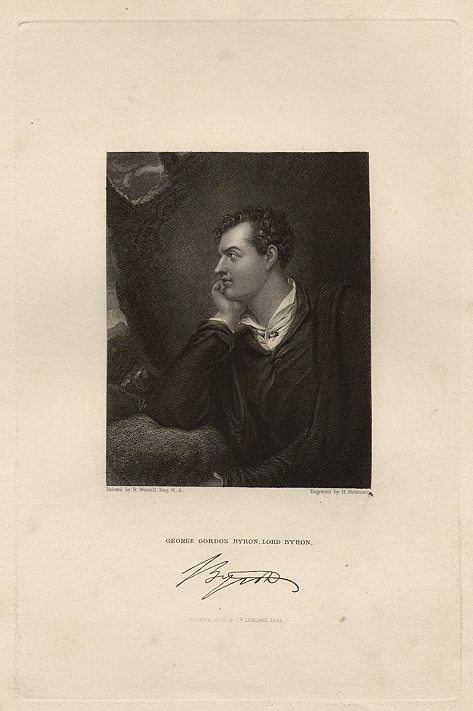

Lord Byron used a Falmouth packet to sail to Lisbon in 1809. He stayed in the town for over a week, lodging in rooms in Church Street, before sailing on July 2nd on a ship commanded by one Captain Kidd. He wrote to his friend Francis Hodgson on 25th June 1809 ‘The town of Falmouth, as you will partly conjecture, is no great ways from the sea. It is defended on the sea-side by tway castles, St Maws and Pendennis, extremely well calculated for annoying every body except an enemy.’

A guidebook of 1824 describes the town thus: ‘Falmouth is now become a very important and populous sea-port town… The Harbour, which is considered one of the best in England, is so commodious and sheltered, that the most numerous fleet may therein ride in safety…. The town is built along the western shore of the harbour, the houses forming a street nearly half a mile in length. Owing to the improvements which have been made of late years, Falmouth has a very prepossessing appearance, and is now inhabited by many respectable families.’

Because of the packet service, lots of ancillary services flourished in the town. From everything to do with the ships themselves like, sail-makers, chandlers, shipwrights, carpenters, etc, to those who supplied the ships for their journeys: butchers , poultry-men, ships bread and biscuit bakers, wine and spirit merchants. Because the packets also carried passengers, hotels, inns and similar hostelries found a place there too.

Today, the packets are long gone, finishing in 1851 after 150 years of service. But Falmouth is still a vibrant and elegant town, many of the houses built in the town’s heyday still survive. I’ve visited a couple of times in the last few years and it is one of my favourite places.

The Custom House Quay is still there, a reminder of all the comings and goings of this busy port.

Falmouth Docks, on the northern shore of Pendennis Point, still play an important role in the commercial life of the town, and walking up towards Pendennis Castle one gets a good view over the docks and the estuary.

On my last trip I was lucky to see a large cruise liner in the harbour. I’m sure today’s passengers on these huge craft have no idea that the origins of cruise ships were the little packet ships that set off here all those years ago.

The main source of income today in Falmouth is the tourist trade. In summer the quaint streets are crowded with holiday-makers; the lovely beaches and coves of the Cornish coast are a magnet for people who enjoy the seaside, while the harbour is home to ‘yachties’ and those who like messing about in boats.

Though I’m not a keen sailor, I can recommend taking the ferry across to St Mawes and back, or how about a trip up river to the picturesque town of Truro? Even a shopping trip to the supermarket at Ponsharden, a commercial area on the outskirts of Falmouth, turned into an adventure for me — not only is there a bus service from here back into town, but also a boat service. You can guess which option I chose.

Well, I hope you’ve enjoyed my brief description and history of Falmouth. In a future post I intend to share with you some more of my discoveries about the Falmouth Packets.

Have you ever visited Falmouth? What did you think, and have you got any recommendations for my next trip there?

- The word ‘pacquet’ is from the French and alludes to the way in which dispatches were packed and sealed. Eventually the word became ‘packet’ and was associated with the actual service used for sending the dispatches, and then the vessels themselves.

If you enjoy historical romance, I’ve written a series of Regency stories. I’ve also written contemporary romance stories with lots of mystery… and a few ghosts.

All my books are available on Amazon and Kindleunlimited.

You can discover them here.

Sources

Old Falmouth, Susan E. Gay, Headley Brothers, London, 1903

Excursions in the County of Cornwall, F.W.L. Stockdale, London, 1824 (reprint D. Bradford Barton, Truro, 1972)

Life in Cornwall in the Early Nineteenth Century, R.M. Barton,Truro 1970

The Falmouth Packets 1689-1851, Tony Pawlyn, Truro, 2003

We have just bought a house previously owned by a Lisbon line packet ship commander. If you’re still researching this do please get in touch. The house and “barns” are starting to tell a most intriguing story… your insight and knowledge would be an enormous help and I think you’d be fascinated in the buildings

How fascinating, Helen. Not sure how much help I can be, but I’d be happy to learn more about what you’ve discovered. Will send you an email. Best wishes, Penny

Thanks so much for this information. Just seeing if I could get a breakdown on the time taken for a military message created in London to get to the allied camp in Portugal/Spain during the peninsular wars. You have mentioned 4 days from London to Lisbon…do we know how long did it took to get from London to Falmouth and was this via telegraph or via stage coach…? And that final leg from Lisbon to the camp…is there a rule of thumb perhaps for distance over time for the horses…do you know of any information on that leg of the journey?

Hello Tim,

Thank you for your comment. Sorry it has taken me so long to reply, but I’ve been very busy trying to finish my next book.

I’m afraid that the quote I used detailing when the mails were made up in London for the various destinations refers to the time it took mail to reach Falmouth, not the final destination. London to Lisbon in 4 days would have been impossible. I apologise if this was not clear.

Even by 1798, it was still taking an average of two and a half days for mail from London to reach Falmouth.

The only exception to this journey time (that I know of) is Lt Lapenotière’s famous 271 miles non-stop journey from Falmouth to the Admiralty in London with the Trafalgar Dispatches, which he achieved in under 38 hours.

As far as journey times from Falmouth to Lisbon are concerned, I’ve been able to ascertain that they took about a week (from History of the Post Office Packet Service Between the Years 1793-1815, by Arthur H. Norway, (1895).

I’m afraid that the time mail took on the final leg from Lisbon to a military camp would have depended on a lot of variables: where the camp was, weather, enemy action, etc. Of course, in Portugal, Wellington had ensured that a signalling system was installed (the Balls and Flags system) on the Lines of Torres Vedras, which would have helped.

I hope this is of some help,

Best wishes, Penny