A major contributing factor to Wellington’s success in his Peninsular Campaign was the role played by the British Royal Navy.

The British economy at the time of the Napoleonic Wars was based on trade, insurance, and financial services. Portugal, and access to its colony of Brazil, was crucial to Britain’s commercial interests. British woollen goods were purchased by Portugal and exported to Brazil, with any imbalance in payment made up by specie (coinage) shipments direct from Brazil to England by the Royal Navy and the Falmouth packet service. It is estimated that by the mid 18th century more than £1,000,000 a year was coming into Falmouth.

Why was specie important? Well, it gave Britain the ability to pay its allies in hard cash, and enabled Wellington to pay his army. Being able to purchase food from locals, rather than resorting to taking it by force, was an important element in securing and maintaining their support for what was in effect an occupying army.

Wellington himself acknowledged this fact.

‘Without pay and food, they must plunder; and if they plunder they will ruin us all.’

The Navy’s beneficial role in Britain’s Portuguese actions actually commenced prior to the British army setting foot there. When France ordered Portugal to close its ports to British ships in 1807, Britain reacted by making a secret deal guaranteeing to assist the Portuguese royal family and its navy to flee to Brazil if France invaded.

The benefits to this action would not be one-sided, as far as Britain’s interests were concerned. It would not only remove the Portuguese fleet out of the grasp of the French, it would also guarantee a favourable ally in South America.

Canning, the Foreign Secretary, sent Sir Sidney Smith with his fleet to ‘encourage’ the evacuation of the court from Lisbon on 16 November. A combination of threats, diplomacy, and the knowledge that French troops were advancing, finally persuaded the Portuguese court to leave.

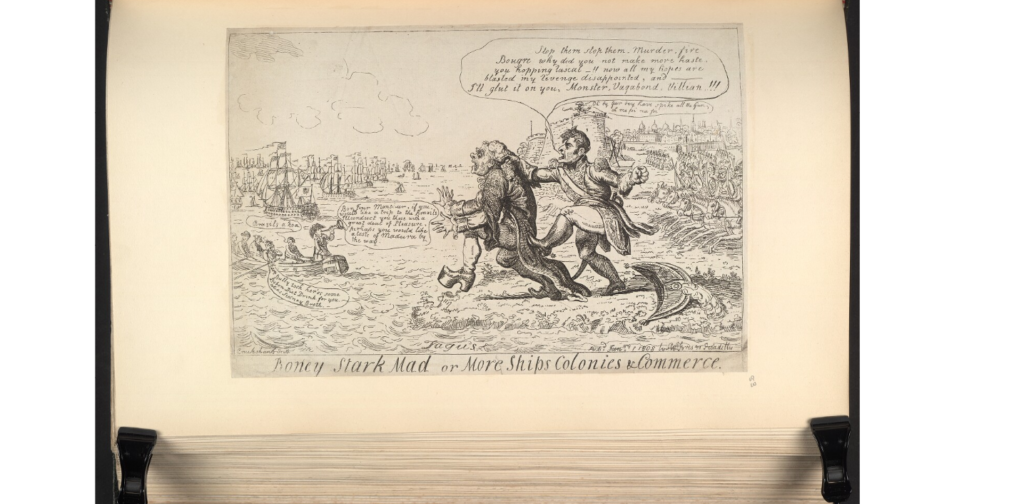

Without recourse to offensive action, the British Royal Navy had prevented more ships falling into French hands.

Another important tactic used by the Royal Navy for impeding French advancement was blockading. In this way, the French could be prevented from accessing their own strategic bases. Sicily was garrisoned with 16,000 British troops, necessary to prevent the French from moving further into the Mediterranean. Cadiz was another port being blockaded, as well as Ferrol, Vigo, and Cartagena.

Along the Catalonian coast, Lord Thomas Cochrane was occupied in making trouble for the French, by attacking their shore installations and signal towers, bombarding French columns, and giving aid to Spansh guerillas. To do this, Cochrane had established his own base in a safe harbour at Rosas. Understandably, the French decided that to rid themselves of Cochrane’s actions, they needed to secure Rosas for themeselves.

Getting news of these French intentions concerning Rosas, a British contingent under the command of Captain John West, was sent to help defend the town. West, during the course of action there, became one of the few naval officers ever to have had a horse shot from under him. The French however were determined to take Rosas, and when it became evident to the British that a long siege might be in prospect, they decided to withdraw. Lord Cochrane and his fleet arrived, the British forces were evacuated, leaving Rosas to the French.

In July 1808, at the start of the Peninsular Campaign, the Royal Navy played a crucial role in landing the British military forces, under the command of Sir Arthur Wellesley, in Portugal. Mondego Bay, although not ideal, was considered the best option by Wellington. He knew that three-hundred marines had already been landed, and were currently occupying the nearby fort of Figieira. They would be able to provide some protection to the vulnerable landing troops.

There was a heavy surf when the first soldiers disembarked from the ships; more than sixty men were lost when their boats overturned, weighed down by their heavy packs. In the days to follow, more ships arrived, and it took almost three weeks for the full consignment of troops to be brought safely to shore.

The French, made aware of the British landings, moved to put a halt to this. They didn’t get as far as Mondego, instead they met with Wellesley’s forces at Vimeiro, where they were defeated. The landings continued unimpeded, and by the end of August 30,000 British troops were on Portuguese soil.

After the French defeat, the infamous Convention of Sintra was signed on 30th August, whereby it was agreed that the French would be allowed to depart back to France without further conflict. They were even transported there by the British Royal Navy.

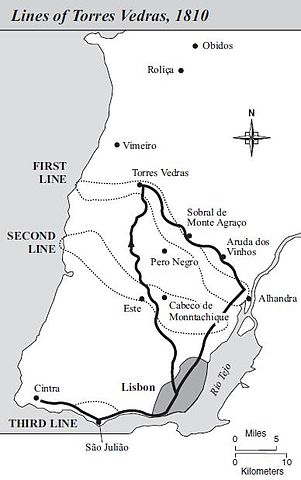

However, the Royal Navy’s involvement in the Peninsular campaign didn’t end there. The Navy was instumental in Wellington’s success in consolidating his operational base in Lisbon, and the successful operation of the Lines of Torres Vedras (see my previous post). Five of the signal stations forming the Lines of Torres Vedras were manned by navy personnel, who transmitted information across the country using a system of naval signals (the army had no equivalent system).

Near Lisbon, a flotilla of flat boats was established on the River Tagus by Admiral Berkeley to transfer supplies upriver to the British army contingent at Abrantes, a journey that took only ten hours, instead of the three days it would have taken by land. Abrantes was a strategic position – whoever held Abrantes controlled access to Lisbon, therefore it was crucial that the British hold on Abrantes was maintained.

Throughout the Peninsular Campaign, the Navy continued to play an important role, even rescuing British troops when necessary. In 1809 Sir John Moore had been tasked with distracting the French in Spain, but he was forced to flee with his army to the coast to try and embark with his men before the French could catch up. Transport ships were waiting for him at Vigo, but instead he headed for Corunna, where there were only British store and hospital ships.

Undaunted, he started to evacuate his sick and wounded, but the French were getting closer, pressing the rearguard of his army who were trying to hold them off. Luckily, the next day the British transport ships finally arrived after being delayed by bad weather, and it was left to a naval commander, Captain James Bowen, to oversee the evacuation. Moore and his men managed to hold the French off long enough for 28,000 of his men to be rescued, but Moore lost his own life in the process. It could be argued that, if the navy had not turned up, Britain would have lost a substantial part of her military forces, causing political upheaval at home and possible capitulation to Napoleon.

Wellesley certainly recognised the importance of Royal Navy support. His own supply line stretched all the way back to Britain. Convoys requiring naval protection were constantly shuttling between the two countries, bringing men, supplies, and horses, to Portugal, and transporting the wounded, the sick, and prisoners, back to Britain.

I’ll leave the last words on the British Navy to Wellington.

‘If anyone wishes to know the history of this war, I will tell them that it is our maritime superiority [that] gives me the power of maintaining my army while the enemy are unable to do so.’

For anyone interested in reading a fuller account of the Royal Navy’s role during the Napoleonic Wars see: A History of the Royal Navy The Napoleonic Wars, by Martin Robson, I.B. Tauris & co, 2017

If you enjoy historical romance, I’ve written a series of Regency stories. I’ve also written contemporary romance stories with lots of mystery… and a few ghosts.

All my books are available on Amazon and Kindleunlimited.

You can discover them here.

I have to get to grips with the availability of specie, so this is really helpful to me. Thank you, Penny 🙂

Glad you found it helpful, Charlotte!