Have you heard of the Royal Military Canal? Up to fairly recently, I hadn’t. An entry in the Gentleman’s Magazine for December 1810 brought it to my attention. It reported that a soldier had drowned in the canal, having fallen in when it was dark.

The report didn’t mention the site of the tragedy, stating only that the victim belonged to the Staff Corps, stationed at Hythe. Intrigued, I decided to investigate, and discovered the Royal Military Canal.

Report in the Gentleman’s Magazine

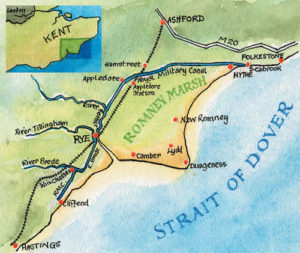

Unlike most other canals, built by wealthy landowners or entrepreneurs, to convey goods across the country, this twenty-eight mile canal running from Seabrook, Kent to Cliff End, Sussex, was built for defence. In 1804 Britain was at war with France. Only the Channel, the British Navy, and a line of Martello towers along the coast from Folkestone to Eastbourne, stood between Britain and Napoleon’s massed troops on the French side.

The-Royal-Military-Canal-www.royalmilitarycanal.com_.jpg

Romney Marsh was more or less undefended, even though this was the location where it was expected Napoleon would send his invasion army. For many years, it had been thought that, by flooding the low-lying Marsh, it would be easy to contain any enemy troops who landed there.

However, as the reality of the threat grew, it became evident that this solution would not be easy, or quick, and it would cause damage to the land. Also, if implemented in the event of a false alarm, the resultant unnecessary devastation would be expensive to remedy.

But Lieutenant-Colonel John Brown, Commandant of the Royal Staff Corps, came up with an ingenious plan. He proposed building a nineteen mile long canal from Seabrook, Kent to the River Rother in Rye, to partly encircle Romney Marsh. The canal would have kinks, to allow troops to fire along it, should the enemy attempt to cross it. In this way, it was hoped that any invading troops could be contained and repelled.

One of the kinks in the canal

On September 26th 1804, the Duke of York, who was the Commander-in-Chief of the British Army, met with William Pitt, the Prime Minister, to discuss the viability of this canal. They were both enthusiastic. It was optimistically estimated that the canal would take less than a year to construct, and could be ready as soon as June the following year.

A consultant engineer was appointed and Pitt endeavoured to convince local landowners who would be affected by the construction of the canal, that they would be doing their patriotic duty by supporting the scheme.

Patriotism wasn’t the only motivator. It was stressed that, once hostilities were over, the canal would greatly improve the Marsh by providing drainage in winter, and providing water for dry summers. Pitt’s efforts paid off. The locals were convinced by his reasons and the canal became known as ‘Mr Pitt’s Ditch’.

Work began on 30th October 1804, but matters were not straightforward. Poor weather conditions, a shortage of workers, and disputes between the consultant engineer and the contractors, made the original deadline of September 1805 highly unlikely. By May 1805, when only six miles of canal had been built, the contractors and the engineer were all dismissed from the project. They were replaced by the Quartermaster-General’s department and the originator of the scheme, Lieutenant-Colonel Brown, was put in command.

Although civilian navvies continued to do the digging, the military built the ramparts and the banks. Steam engines were brought in to deal with the constant flooding which threatened the progress of the canal, but apart from this innovation, the entire canal was constructed by hand. At one point, 1,500 men were working on the project.

Despite the increased speed and efficiency due to the change of command, and the use of army personnel, the canal was not completed until April 1809. In addition, the original dimensions were reduced, making it mostly half the originally intended width.

A view of the canal

Unfortunately, by the time of its completion, the canal’s original purpose was redundant. The threat of invasion had disappeared. Napoleon had abandoned his plans for Britain, his interests now lay in Europe. The state-funded canal became an embarrassment to the Government, being considered a total waste of public money.

It was decided that the best way to recoup the cost of £234,310, was to open the canal entirely for public use, something that the Government had been trying to do since 1807, by initially allowing the transport of goods along the canal for a fee. Passenger traffic was also permitted.

Alas, despite the charging of tolls for both the canal and the military road, the revenue was insufficient. Later on, competition from the railways further reduced passenger numbers. The fiscal burden increased when the mounting costs of maintenance were added to the original construction costs.

By the 1860s, the Government finally divested itself of responsibility for the canal by leasing it in sections to different owners, only taking it back in the 1930s, when the War Office became concerned about the threat of another invasion. Today, the Canal is used by the Environment Agency to manage water levels across much of the Marsh.

Although, in one sense, the canal can be deemed a failure, never having been utilised for its original and primary purpose, today it does fulfil one of its intended functions magnificently. It drains the Marsh in winter when floods threaten, and provides vital water for irrigation in summer. It is also a habitat for many forms of wildlife and parts of it are designated as Sites of Scientific Interest.

It also affords many leisure activities: walking along the banks, boating, and fishing — the canal being considered one of the best places in Kent for coarse fishing. In fact the canal had been stocked with fish way back in 1806, when officers and members the gentry were permitted to fish in summer from the tow-path side.

From the sad report of an unnamed soldier’s death by drowning, I have discovered not only another inviting place to visit, but also a tangible reminder of the Napoleonic Wars.

Do you know of any sites that have connections to the Napoleonic Wars, which may not be so obvious today?

Sources

P.A.L. Vine, The Royal Military Canal, 1972, David & Charles Publishers

The Royal Military Canal website

One Response