Researching for my next book, I’ve discovered a lot about the Falmouth Packet Service, and thought I’d share it with you here.

The ‘King’s Post’ had been an established entity for some years, set up to carry mail such as State letters and dispatches both on inland routes and internationally to and from Great Britain. These State letters and dispatches were known as ‘packets’ after the French word ‘paquet’, which referred to the way in these items were packaged and sealed.

In 1674, the then Post Master General, Colonel Whitley, proposed setting up a maritime route to Spain and Portugal from Plymouth or Fowey; he also envisaged that the service would carry passengers and goods. By the 1680s, communications between Protestant Britain and the Iberian Peninsula and the Mediterranean became difficult, due to the conflict with Roman Catholic France, who cut off the land routes to these places. Because a major part of Britain’s trade links lay with Spain and Portugal, and via them to the Americas and West Indies, an alternative route now had to be found. However, it was not until the late 1680s to the early 1690s that the first service between Falmouth and the Groyne of Corunna was established. The first two packet ships were named Spanish Allyance and Spanish Expedition. By the 1830s, there were forty vessels sailing to Lisbon, Gibraltar, Malta, Corfu, Bermuda, Leeward Islands, Windward Islands, Mexico, Rio de Janeiro, and Buenos Aires.

The packet service was essentially a department of the General Post Office, under the jurisdiction of the Post Master General. A Packet Commander would be engaged by the General Post Office to undertake the required voyages in his own manned and equipped ship, at a hire of £1800 per annum. The ships had to be approved by the Postmaster General, and if a ship was being built specifically for packet service, it would be inspected at varying stages to ensure it complied with the Post Office specifications.

However, as the service grew, more staff were required to oversee its administration. In the 1790s the post of Inspector of Packets was established. This person’s job was to inspect the construction of new packet ships, assess any damage to ships sustained while in service, and calculate whether any compensation was due. They were also expected to verify the suitability of other ships hired for service in emergencies.

Packet Agents, usually local men, were responsible for the receipt and dispatch of mail between Falmouth and London and the victualling of the ships. They were also expected to implement the Post Master General’s instructions, and to ensure that the packet commanders complied with the terms of their contracts. It was in the Agent’s power to award contracts to favoured local business men to supply the victuals and other materials needed by the ships — something that could be open to abuse.

At various times, other staff were employed at the Falmouth packet station. During the war of 1701-1713, a shore-based surgeon was contracted to care for the sick and wounded seamen, who would be lodged around the town. By 1823 there was a searcher and inspector of packets (employed to suppress smuggling on the ships), a storekeeper, a chronometer maker, and a collector of monies and accounts’ keeper, in addition to a number of clerks.

Packet commanders, the men who owned and sailed the packet ships, were prominent and important members of the community. They wore uniforms similar to Royal Navy officers, even though there was no requirement for such a uniform. They could afford the best houses, with many of the Falmouth commanders settling in Flushing, a select area close to Falmouth. Many of present-day Falmouth’s fine historic houses are a legacy of wealthy packet boat commanders.

However, packet commanders’ wealth was not due to their pay, as it was a relatively modest rate, unaltered during times of peace or war. They were able to derive a large supplementary income from the carriage of passengers and freight, usually bullion. The most popular, and therefore the most lucrative route was Lisbon, particularly towards the end of the Peninsular Wars. This route was the preserve of senior packet commanders, and it was the aim of most commanders to make their way up the ‘list’ and be appointed to the Lisbon route. By the time Napoleon was finally defeated this route declined in popularity, but new routes to South America opened up, offering opportunities to less senior commanders.

Crews of the packet ships were a mix of older, experienced sailors, and young men who wished to make their lives at sea. Crews could also include a proportion of foreign seamen, even though this was strictly forbidden. Because sailings were regular, the packet service was an attractive option for family men, or those looking for stability, although things did change during times of war.

When the Royal Navy introduced press gangs in Falmouth, service on the packets became even more attractive, as the men employed thus were protected from impressment. Crew would be kept on a ship’s books even after the end of a voyage, working on the docked ship, having spells of shore leave, and safe from the press gangs. However, if a packet ship was lost, this protection to the crew was also lost. When one packet ship was wrecked, its crew was taken up by another merchant ship and brought back to Spithead, where the press gang immediately boarded and ‘pressed’ all the packet crew into naval service.

As to the mail itself — the whole reason for the existence of the packet ships — this was the last item to be placed on board at the start of a voyage and the first item to be landed at the destination.

The Mails made up in London on Tuesday, arrive on Friday; and those made up on Wednesday, arrive on Saturday.

During war time the mail was kept on deck, ready to be ditched overboard in case of boarding by the enemy. It was thought better to lose important documents, which had usually been duplicated and dispatched on a following packet ship in any case, than to let it fall into enemy hands.

Mail was stored in weather-proof leather portmanteaus, made to standard sizes. These were weighted with iron to ensure that they would sink if they needed to be jettisoned overboard. If a packet ship looked likely to be engaged in action with an enemy, the portmanteau was hung over the side, ready to be cut away if required. Sometimes portmanteaux were shot down by enemy fire and lost, but ocassionally one would not sink, and would fall into enemy hands. If this happened, the ship’s commander would be called to account by a committee of his fellow captains.

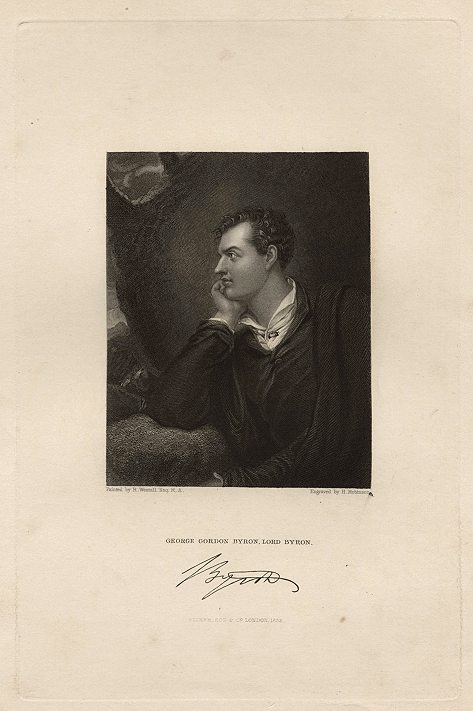

‘I shall not survive the racket

Of this brutal Lisbon Packet.’

By 1836 commercial steam ships were posing competition, running services between London and Lisbon and other ports in Spain. In 1840 the Post office issued a notice that packet mails would henceforth be dispatched by steam vessels from Liverpool instead of Falmouth. This was the beginning of the end for the traditional packet service and the start of what we now think of as cruise lines. In May 1851 the final packet ship, Seagull, arrived in Falmouth from Rio de Janeiro, carrying only eight passengers and a small amount of mail. After more than 150 years of service, it was the end of the line for the Falmouth Packet Station, driven out of business by the faster steamships.

Sources

The Falmouth Packets 1689-1851, by Tony Pawlyn, Truran, 2003

History and Description of the town and harbour of Falmouth, by R. Thomas, Falmouth, 1827

The History of Falmouth, by Dr James Whetter, Redruth, 1981

Old Falmouth, by Susan E. Gay, London, 1903

One Response