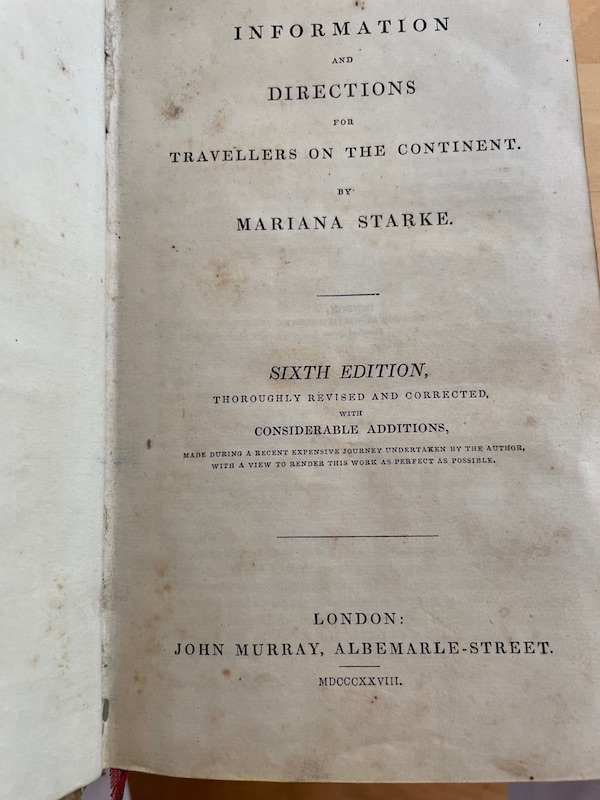

A few months ago I was fortunate enough to purchase a copy of Mariana Starke’s (1762-1838) Information and Directions for Travellers on the Continent. The edition I now proudly own is the 6th edition of her work published in 1828.

Mariana was born in Epsom and was the eldest daughter of Richard Starke who had been an officer of the East India Company and the deputy-governor of Fort St David, Madras until 1756. In 1792 Mariana and her family moved to Italy, remaining there for seven years. The travel notes she made during her stay became the basis of her first publication Letters from Italy in 1800.

Recognising that there was a need for more practical information for travellers abroad, Starke contacted another publisher, John Murray, and the idea of a guidebook was born. As a woman, Starke was criticised for compiling such a book, even though her work went on to become the forerunner of the modern travel guidebook.

Mariana’s publication was comprehensive, advising would-be travellers of not only what they would find in foreign parts but also the legal requirements for getting there, the best times to visit, and how to maintain their health when abroad.

Pisa was recommended for those suffering from pulmonary complaints, its climate being far superior to any other Italian city, particularly during the months of October up to April. Naples was not advised for persons suffering from any stage of decline due to ‘the quantity of sulphur with which its atmosphere is impregnated’.

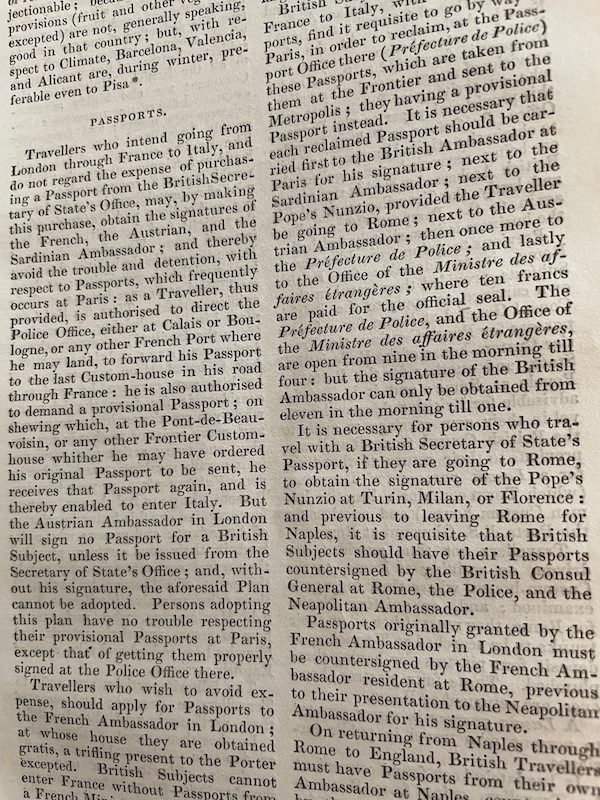

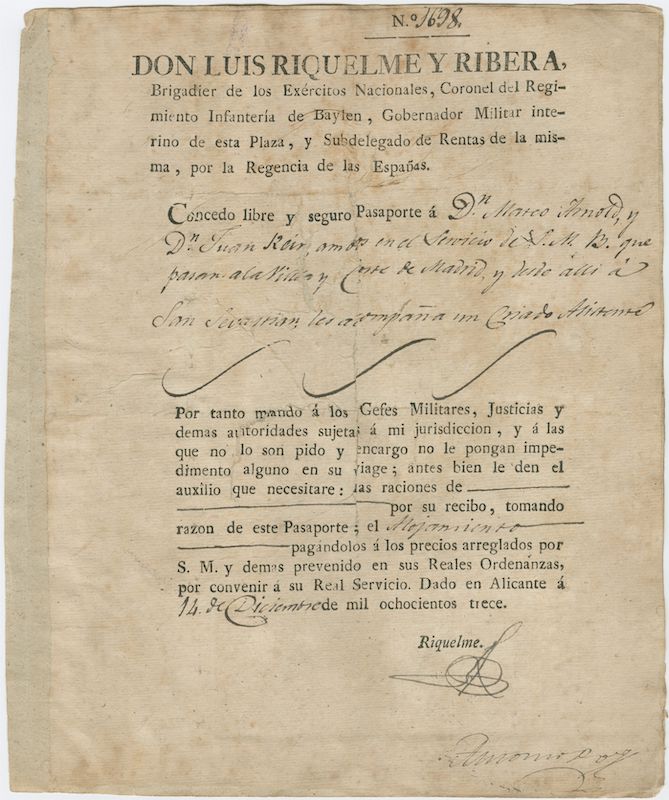

Of course, just like today, passports were required for foreign travel. Unlike now, if a Regency traveller was intending to journey through several countries a separate passport was required for each one. Indeed, the whole system of getting the necessary documentation, although clearly explained in the guidebook, would certainly have made me think twice about journeying abroad.

At least nowadays, although passports are not cheap, they cover all destinations and we don’t have to tip the doorman. How about this advice for those wishing to visit France.

‘Travellers who wish to avoid expense, should apply for Passports to the French Ambassador in London; at whose house they are obtained gratis, a trifling present to the Porter excepted.’

Travelling in Italy was particularly complicated: ‘it is requisite that British Subjects should have their Passports countersigned by the British Consul General at Rome, the Police, and the Neapolitan Ambassador’ – and that was only to enable them to travel from Rome to Naples!

Being a seasoned traveller herself, Mariana knew how a naive visitor could easily be relieved of his money. She recommended that tourists travelling in their own vehicles should include in their party ‘an active intelligent English Man-servant, who understands how to grease and chain wheel, and likewise how to load and take care of English carriages.’ Any local person employed to assist travellers would cost more because of taxes imposed on such employment.

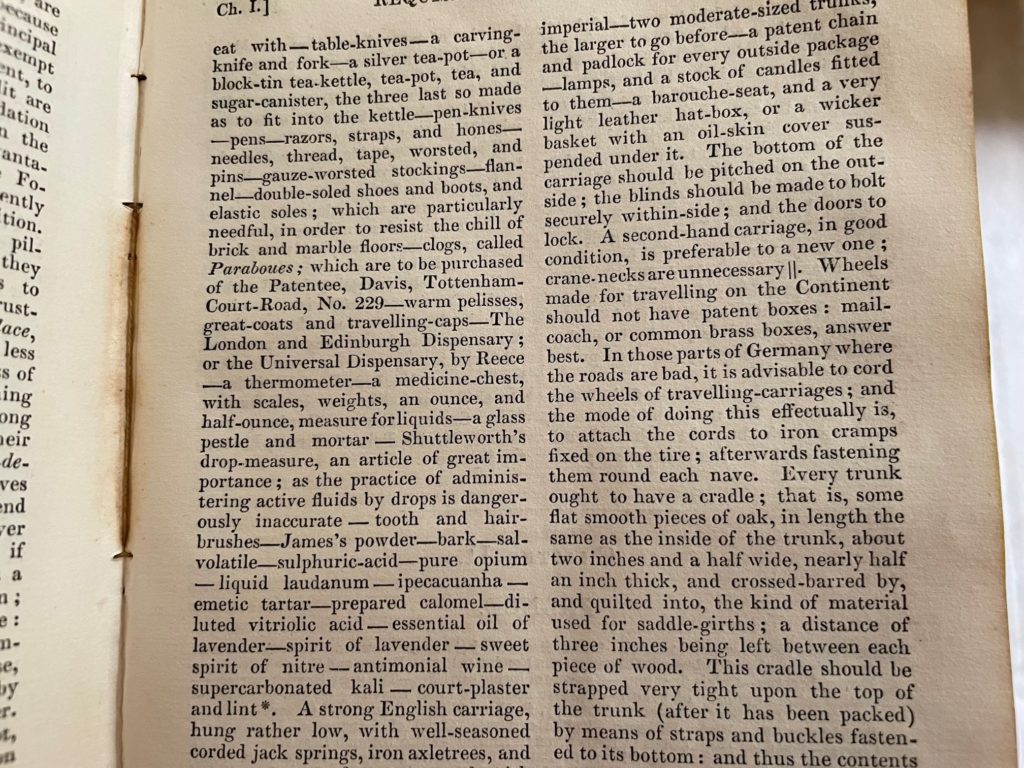

The list of items that the guidebook specifies as being useful for foreign travel is certainly extensive. From bedding and locks for bedchambers, writing desks and coach seats, to tinder box and matches, lanterns, towels, table-cloths, cutlery, and napkins. Even a kettle and teapot! And that’s before Mariana mentions the types of clothes to pack – warm pelisses, great-coats and travelling caps.

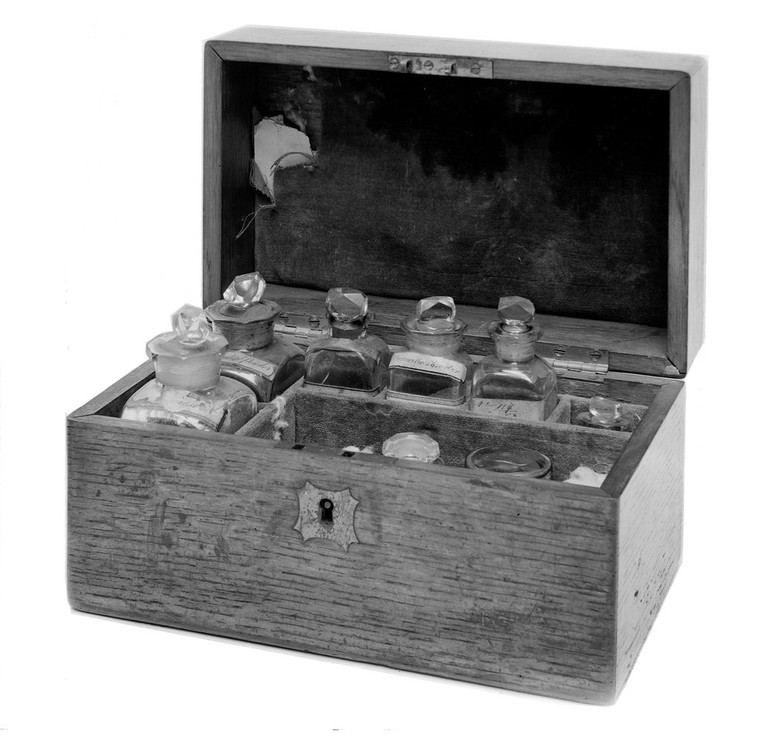

A medicine chest for health emergencies was a must, together with a copy of ‘The London and Edinburgh Dispensary ‘. The chest should be packed with scales and weights for both dry amounts and liquids, a thermometer, and a pestle and mortar. From the list of necessary items we can get an idea of what was in a well-regulated Regency household’s first aid box: bark, salvolatile, sulphuric acid, pure opium, liquid laudanum, ipecacuanha, emetic tartar, prepared calomel, diluted vitriolic acid, and essential oil of lavender.

In case you’re wondering, ten drops of oil of lavender sprinkled on a bed ‘will drive away fleas’ and five drops of sulphuric acid put into a decanter of bad water ‘will render the water wholesome.’

Once everything was packed, a Regency traveller could then address the question of how to reach the Continent. But I’ll leave that advice for another post – all that packing has left me quite exhausted.

Do you pack for every eventuality as Mariana recommends, or do you prefer to travel light?

Images

Photos of title page, pps. 439, 441 (author’s own)

Travelling Carriage: unknown artist, after James Pollard, 1792–1867, British, Coaching: Travelling Carriage, 1835, Aquatint, hand-colored, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1985.36.854

Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, Travelling in France, between 1785 and 1789, Watercolor, pen and black ink, gray ink, and graphite on moderately thick, slightly textured, blued white, laid paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B2001.2.1134

A passport: Spain. Sovereign (1813-1833 : Ferdinand VII). Passport of Matthew Arnold and John Keir for travel to Madrid and San Sebastian. Alicante, Spain, 1813 December 14. Yale Center for British Art

Customs House at Boulogne: Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, Customs House at Boulogne, 1790s, Watercolor with pen and gray and black ink over graphite; verso: graphite on medium, moderately textured, blued white, laid paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1975.4.1721

Medicine chest with glass bottles with silver lids, 4 labelled, one spare silver lid, 2 packets of weights, silver gilt funnel, and ornate decorated silver gilt cup, possibly Irish, late 18th century. grey background. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) Science Museum, London

Medicine Chest containing bottles. Credit: Wellcome Collection. Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

A medicine chest owned by Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington (1769-1852). The chest was supplied by John Bell and has the name ‘Arthur Wellesley’ written on the labels of the bottles. The chest contained tincture of rhubarb, ether and other common medicaments. Wellington had the chest with him throughout the Peninsular Campaign at Waterloo. Licence: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) Credit: M0000155: Duke of Wellington’s medicine chest.

How golly wonderful! Thank goodness we don’t have to pack so much these days while travelling. Can you imagine what the lady would think of our travel plan these days. Would she be shocked or pleased?

I’m really glad we don’t need to pack as much these days, Paula. I always take too much as it is!I reckon those Regency ladies would be really shocked to know that most of us only take one suitcase.

Exactly and we hopefully don’t have to worry about fleas and bedbugs 😱

Eeek! Yes, we’re very lucky that fleas are not as common these days, though I have read that bedbugs are becoming a bit of a problem again.

Oh no! I wonder why! Have we let standard slip so badly. Maybe with more people sleeping rough, more crowded houses etc.

A very interesting blog which I enjoyed reading; thank you.

Thank you, Marcia. I’m glad you enjoyed it. For a Regency lady, Mariana must have undertaken a lot of travelling and research to gather all the information she used in her book.