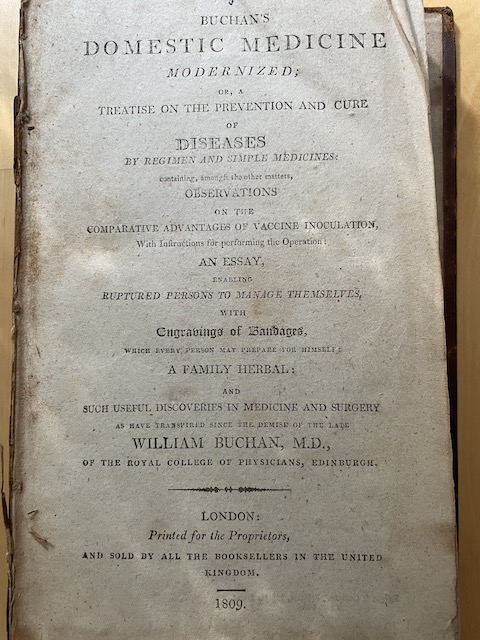

Having recently purchased one of the most popular domestic medical advice books of the Regency period – Buchan’s Domestic Medicine Modernized– I thought I’d look at a few common ailments and see how they were treated in the past. If you’re a bit squeamish, look away now!

Fevers

According to Buchan, fevers are usually caused by infection, errors in diet, unwholesome air, violent emotions of the mind, excess or suppression of usual evacuations, external or internal injuries, and extreme degrees of heat or cold. It is interesting to see that at that time violent emotions were credited with causing a fever.

For individuals who have a fever due to catching a cold this book recommends keeping warm, drinking diluting liquors, and bathing the feet in warm water. However, if the fever is accompanied by spots or a rash, the poor patient should be treated by ‘repeated vomits’.

Eurghh

To be fair, this book contains lots of good advice that still holds true today, such as ensuring that there is ‘a constant stream of fresh air’ entering the patient’s sick room. Buchan is generally not in favour of bleeding as a treatment for fever, as ‘there is now hardly one fever in ten where the lancet is necessary.’

Intermitting fevers or agues are a different matter and were said to be caused by ‘effluvia from putrid stagnating water’. Eating too much stone fruit, a poor watery diet, and even damp houses were also said to cause fevers.

The initial treatment is rather drastic – a full cleansing of the stomach and bowels! This is as gruesome as it sounds, with ‘a dose of ipecacuanha’ administered to make the patient vomit. Alternatively, though less effective, ‘a dose or two Glauber’s salt, jalap, or rhubarb’ is recommended. Purging the body in this way was intended to make the application of other medicines more efficacious.

Once the patient was suitably purged, Peruvian bark could be taken. Also known as Jesuit’s bark, this contained quinine, a well-known remedy used for malaria to this day. The bark was taken in the form of powder, mixed ‘with a little syrup of lemon… in a glass of red wine, a cup of camomile tea, water gruel, or any other drink that is more agreeable to the patient’.

Buchan warns that if an ague is not properly cured it could degenerate into a different disease such as dropsy or jaundice. He lists a few discredited fever cures, such as spiders, cobwebs, snuffings of candles (whatever they are) and insists that Peruvian bark is ‘The only medicine that can be depended upon’. More importantly, according to Buchan it can be used with safety.

Children with fevers should wear ‘a waistcoat with powdered bark quilted between the folds of it’ or they should be bathed in a decoction of bark.

Consumption

Buchan asserts that this illness is more likely to affect ‘young persons between the age of fifteen and thirty, of a slender make, long neck, high shoulders, and flat breasts’. Unlike nasty medicines, the remedy recommended here is a ‘pretty long sea voyage’ – cruise, anyone? Chickens and other young animals that can be kept alive on board should accompany the patient to ensure a healthy diet.

Apart from fresh air and diet, severe cases of consumption required more drastic measures. Buchan recommends bleeding for this as it was thought to relieve coughing. Pills made from ‘fresh squills, gum-ammoniac, and powdered cardamum seeds’ or a mixture of lemon juice, honey, and syrup of poppies were also thought to soothe a cough.

In really bad cases, surgery was performed but, ‘as this operation must always be performed by a surgeon, it is not necessary to describe it.’ The book goes on reassuringly ‘it is not so dreadful as people are apt to imagine.’ Really? Without anaesthetic? I’m not convinced.

Teething

Buchan was something of an expert on childhood illnesses, as his first post as a qualified doctor was at a branch of the Foundling Hospital in Yorkshire. He notes that more than ‘a tenth part of infants die in teething‘, and says that teething should be treated in a similar way to an inflammatory disease. Scarily, this includes bleeding, although he cautions that in very young children this should be sparingly performed; purging, vomiting, or sweating are far more preferable. A leech applied under each ear is also effective. A few drops of hartshorn in water is also helpful, especially when ‘three or four drops of laudanum may be added to each dose’.

The poor little mites must have been thoroughly spaced out or unconscious.

Let’s not forget that this is a book intended for domestic use, so people with no medical knowledge or skills would have had access to all the cures and remedies it recommends.

I don’t know about you, but I’m certainly wondering how our ancesters survived at all.

Notes

Domestic Medicine or the family physician – was written by Scottish doctor William Buchan (1729-1805) and was published in 1769. My copy, Buchan’s Domestic Medicine Modernized, was published in 1809.

Images

Henry Dawe, 1790–1848, British, The Life of a Nobleman: Scene the Ninth – The Sick Room, undated, Brown wash and graphite on medium, moderately textured, cream wove paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1986.29.59

John Collet, ca. 1725–1780, British, The Doctor’s Pill, undated, Graphite, watercolor, pen and black ink, gray wash on slightly textured, medium, cream laid paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.5418

Opium Tincture bottle, image courtesy of Science Museum, London

Fascinating! As you suggest, some of the advice makes sense to us today; other remedies are more dubious. I see you included an image of a medicine manufactured by Burroughs Wellcome, a trail-blazing pharmaceutical company eventually absorbed /morphed into Glaxo Smith Kline. Henry Wellcome was initially a peddler of quack medicines, but I believe the The Wellcome Trust, formed by his will and based in Euston, funds more medical research than the UK government.