As some background reading to my historical stories I’ve been looking at Sir John Moore’s System of Training.

This book by Colonel J.F.C. Fuller D.S.O, published in 1924, outlines the methods of training established by Sir John Moore early in the 19th century.

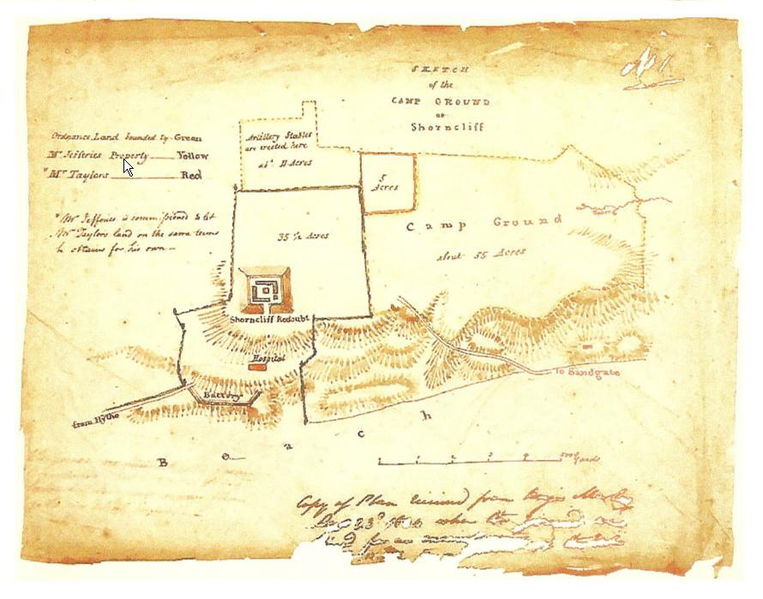

Sir John Moore (1761-1809) was a British Army general, renowned for his reforms and inspired leadership. He introduced light infantry regiments, initiated the cutting of the Royal Military Canal (which I have written about previously here) and established a training camp at Shorncliffe in Kent where light infantry tactics were taught. Moore died in January 1809 while fighting a rearguard action against the French at Corunna. He was so respected that even one of his enemies, Marshall Soult ordered a monument to be erected in his honour.

As someone interested in the Peninsular Wars, I’ve been fascinated in how an army ‘works’. Yes, I’ve heard about forming squares and lines, but I never really understood how it was possible to direct a body of men to move in a coordinated way to achieve these formations – and especially under battle conditions.

Well this book explained a lot. It also explained why Sir John Moore’s troops were renowned for their prowess. He really did start with the basics, ensuring that officers under his command were the best available and up to the task of training others. He weeded out those who were thought to be unsuitable as leaders or instructors. According to Moore, the perfect officer should be alert, vigilant, and moral in character, ‘not exhausted by vicious habits and unable to support the fatigues of war.’

He thought a good commanding officer should get to know his men by inviting them to dine with him and gaining their confidence. But there was to be no over-indulgence in drink – decorum should be maintained.

Young officers, when joining the regiment were placed in the ranks in order to learn the rudiments of drill and to become acquainted with the men they would command.

Every aspect of life was regulated, from getting up in the morning, dress, punishment, meals, drills and fatigues. One of the basic factors of army life was messing. A mess was considered to be the basis for the good order and economy of the regiment, giving to the men ‘comfort and unanimity at meals… the source of friendship and good understanding.’

Every soldier belonged to a mess, and the first rule of each mess was absolute order. ‘No article in a barrack room is ever to be without its place appointed.’ Cleanliness in a barrack room was considered not only good for the men’s health but also if things were clean and in their correct place the men could be ready for service at the shortest notice.

Ten was considered the perfect size of a mess, but some messes had up to eighteen individuals.

All officers were expected to belong to a mess, and those who refused were requested to leave the regiment. Every member of a mess was expected to know how to cook and each took their turn at cooking duties which lasted for twenty-four hours.

Rules were laid down as to plates and cutlery. ‘Every mess is to be provided with three coarse tablecloths, a knife and plate for each man; and every barrack room with three towels, one of which is to be fastened on a roller behind the door for the men to wipe themselves with.’

When dining, it was stipulated that the men should be ‘perfectly clean and well-dressed, with their clothes on, and their hats off, and above all, their hair tied.’

Discipline was another important factor of a soldier’s life, to be attained first by encouragement, advice, and only as a last resort, punishment.

‘Towards well-disposed men the first (encouragement) is always preferable; the latter must, however, be equally appealed to, to bring the bad men into a state of good order.’

So it can be seen that Moore tackled the training of his men by regulating every aspect of their lives. For his time though, he was an enlightened man, caring as much for his men’s welfare as their fighting prowess.

I haven’t even got to the intricacies of the actual drills, marching and other skills yet, so I’ll leave that for another post.

If you enjoy historical romance, I’ve written a series of Regency stories. I’ve also written contemporary romance stories with lots of mystery… and a few ghosts.

All my books are available on Amazon and Kindleunlimited.

You can discover them here.

References

Sir John Moore’s System of Training, Colonel J.F.C. Fuller, D.S.O., 1924, Hutchinson & Co, London

Images

Portrait of Lieutenant General Sir John Moore, by Sir Thomas Lawrence, National Army Museum

https://collection.nam.ac.uk/detail.php?acc=1966-07-22-1

English Barracks:

Thomas Malton, 1726–1801, British, And Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, after Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, English Barracks, 1791, Hand colored etching and aquatint on thick, slighlty textutred, beige, wove paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1978.43.301

Soldiers Carousing at an Inn

Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, Soldiers Carousing at an Inn, undated, Watercolor, with pen and brown ink, gray ink and graphite on medium, moderately textured, cream, wove paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1975.3.82

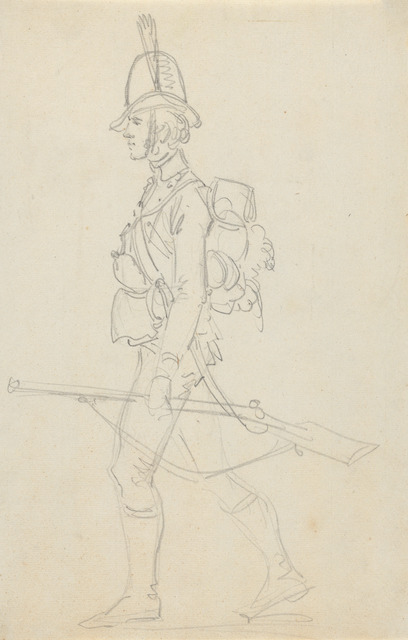

Soldier carrying gun

Joseph Cartwright, c.1789–1829, British, Full-Length of Soldier Carrying Gun in Hand and Gear on His Back, undated, Graphite on medium, moderately textured, blued white, laid paper, mounted on, moderately thick, smooth, beige, wove paper, Yale Center for British Art, Yale Art Gallery Collection, B1984.21.49

Soldiers in St James Park

Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, Soldiers in St. James Park, undated, Watercolor, graphite, pen and brown ink, and pen and gray ink on medium, moderately textured, beige wove paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

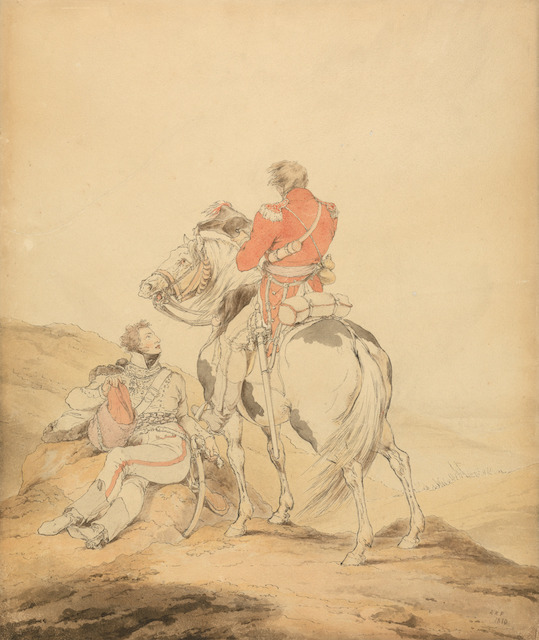

British Officer of the Staff and Hussar

Sir Robert Kerr Porter, 1777–1842, British, A British Officer of the Staff and an Officer of Hussars, 1810, Watercolor and pen and black ink on medium, slightly textured, cream wove paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection

Interesting information! Was this his personal method of training, or was it universally practiced in the forces?

Hi, Riana, Glad you found it interesting. There were a few exponents of such training prior to Sir John Moore, principally Robert Jackson, Inspector-General of Army Hospitals who was very keen on the physical and moral aspects of training. It’s probably true to say that Moore was influenced by several of his contemporaries, however, he refined and created a system that became the basis for later army training, with his emphasis on ensuring that the men under his command were housed well and properly fed.

How interesting that cleanliness and being smart is so important so early in history.

I agree, Paula, and Moore’s ideas fortunately caught on.