I’ve written before about the various ways in which mail got delivered in the past, specifically the packet ships . Now I’m looking at the mail coach service and John Palmer (1742-1818), the mail coach pioneer.

John Palmer was born in Bath to a family of wealthy brewers. As well as the brewery business, his father, another John, also made money from several other ventures, including a theatre. There was a time when father and son did not see eye-to- eye, John junior wished to join the army while his father was keen that he should enter the Church. After a rift between the pair, young John commenced manual work in the brewhouse, something that had a deleterious effect on his health.

However, by the time John was in his late twenties, he and his father were reconciled, and John was given the task of obtaining a Royal Warrant, or Patent, for the theatre the family owned. This involved organising a petition to Parliament, and despite opposition, John achieved this, with a warrant being granted for the Theatre Royal, Bath, in 1768. It wasn’t long before John was also managing a second Theatre Royal in Bristol.

Now, managing theatres meant a lot of travel for John; he needed to secure the services of the best actors and to keep an eye open for emerging talent, so travelling the country using the coach services was something he undertook on a regular basis. As a consequence, he gained a comprehensive understanding of the conditions of England’s roads and an appreciation of the value of good transport. He also realised that individuals were able to traverse the country far more efficiently using coach services than mail sent to the same destinations using the existing mail delivery system.

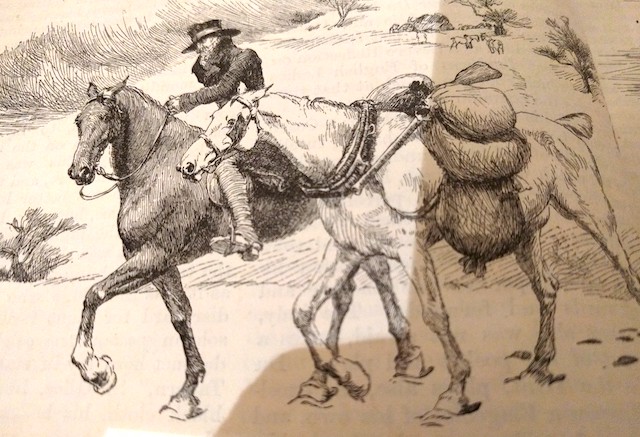

England already had a postal service, which had previously been improved by another Bath man, Ralph Allen. Allen had instigated a system of cross-country posts, which relied on mounted post-boys, who travelled in daylight hours at a rate of six miles per hour.

But this service was creaking and also very insecure, as robberies and hold-ups were frequent. Businessmen who wished to send money or securities by post were advised to cut the notes in half and send each half to their destinations in separate post runs. Not the speediest of processes.

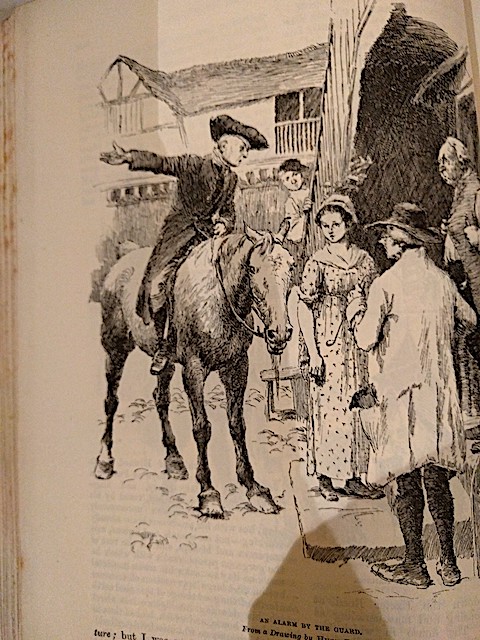

But Palmer had a plan to improve things even further. He proved that a letter despatched by post from Bath on a Monday afternoon arrived in London late on Tuesday, or in some cases, not until Wednesday. By contrast, a letter from Bath sent unofficially at the same time by a coach or diligence would arrive at its destination by Tuesday morning. Palmer’s idea was to contract coach owners to carry not only the mail but also a guard to protect it. He recommended that ex-soldiers could be used as guards, accustomed as they were to discharging firearms, and for their ability to put up with long hours and discomfort.

Palmer’s intention for a reliable, twenty-four-hour, all-weather service would also increase security, for a coach failing to appear at the appointed time would signal a problem, and a search would be put out for it.

As an incentive to coach owners to accept mail contracts, they would be exempt from toll charges. This was not a good thing because it meant that mail coaches did not contribute towards the maintenance of the roads, when in fact, they were the heaviest road users.

To fund this improved system of mail delivery, Palmer decided that postal charges should rise and that the franking privileges of Peers and Members of Parliament should be restricted.

After many objections and delays from both the Government and the Post Office, the Prime Minister, William Pitt the Younger, ordered a trial of the service to begin in August 1784.

The first coach left Bristol at 4pm, was in Bath about an hour later, and arrived at the Post Office in Lombard Street, London at around 9am the following morning, after travelling through the night.

The Bath Chronicle reported on the success of the venture in its issue of 12th August 1784.

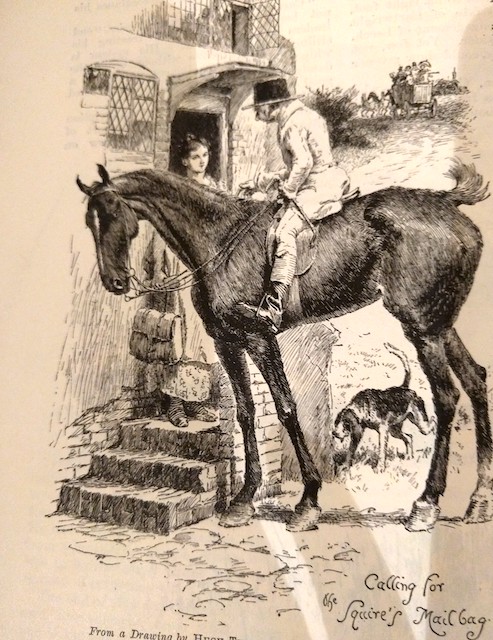

‘The New Mail Coach has travelled with an expedition that has been really astonishing, having seldom exceeded 13 hours in going to or returning from London. It is made very light, carries four passengers and runs with a pair of horses which are changed every six or eight miles, and as the bags at the different offices on the road are made up against its arrival there is not the least delay. The Guard rides with the Coachman on the Box and the Mail is deposited in the Boot. By this means the inhabitants of this City and Bristol have the London letters a day earlier than usual, a matter of great convenience to all.’

The journey time between these two cities halved, while the frequency of the service doubled because these coaches ran every night – a significant improvement on the previous service. Palmer was eager for other routes to be opened up, but it took another eight months for the Post Office to agree to a London to Norwich service.

The reasons for their objections, and the objections of local Postmasters too, was not only their dislike of an outsider – Palmer – changing the status quo, but also that these faster mail coaches eliminated the need for postboy services and other special or express services, from which they would no longer be able to make a profit. They were not keen on other contractors supplying the horses or the disturbance caused by these night-time coaches.

Although there were some objections from the business houses and merchants who were the main users of the postal service, most of them welcomed the change. The clerks at the London Post Office were certainly happy because, with the last outgoing night mails now leaving at 7pm, they were no longer required to remain at their desks until midnight.

By 1797, the mail service had been extended to forty-two routes, and Palmer had been made Surveyor and Comptroller of the Post Office.

Initially, the mail coaches, horses, and drivers were supplied by individual contractors but, by the beginning of the 19th century, the Post Office had its own liveried fleet. But this success was short-lived, for the coming of the railways in the 1830s sounded the death knell of the mail coach service. By the 1840s, many mail coach services were being withdrawn to be replaced by rail services, with just a few regional mail coach services continuing until the 1850s.

John Palmer, despite his continued attempts to reform the Post Office against opposition from the Postmaster General, his superior, was finally dismissed in 1792 with a pension. He returned to concentrate on his life in Bath, becoming the Mayor there in 1796 and 1809. Palmer became the Member of Parliament for the city from 1801 to 1808. He died in 1818 and is buried at Bath Abbey.

Join me soon when I delve some more into the history of coaching and the mail service.

Are you a sender of letters, or do you prefer texts and emails for your correspondence?

References

The Great Road to Bath, Daphne Phillips, Countryside Books, Newbury,1983

John Palmer Mail Coach Pioneer, Charles R. Clear, The Blandford Press Ltd in conjunction with The Postal History Society, London, 1955

Images

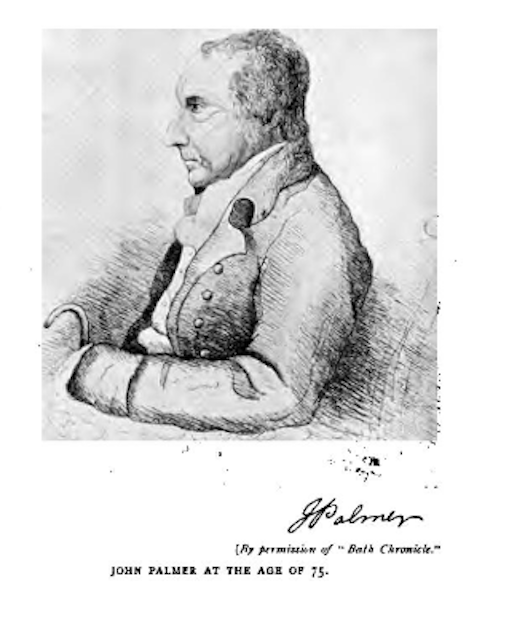

Images of John Palmer taken from: The King’s Post: Being a Volume of Historical Facts Relating to the Posts, Mail Coaches, Coach … by Robert Charles Tombs, W. C. Hemmons, 1905 (from https://archive.org/details/kingspostbeinga00tombgoog/page/n91/mode/1up)

Henry Pyall, 1795–1833, British, after James Pollard, 1792–1867, British, Coaching: A North East View of the General Post Office, with the Royal Mails (& Carts) preparing to Start, 1832, Aquatint, hand-colored, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1985.36.852

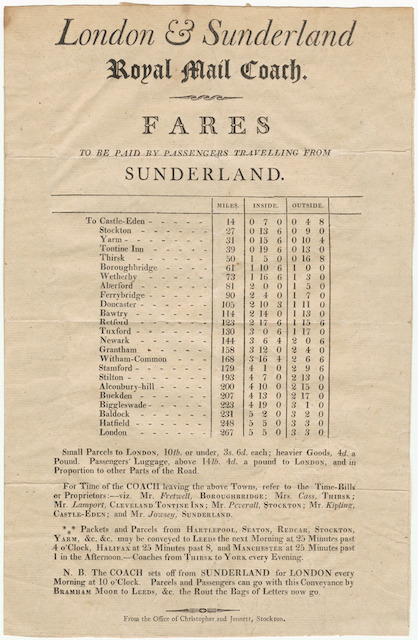

London & Sunderland royal mail coach: fares to be paid by passengers travelling from Sunderland., [ca. 1800]

Samuel William Reynolds, 1773–1835, British, after George Morland, 1763–1804, British, Coaching: The Mail Coach, 1801, Mixed engraving, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1985.36.730

Charles Cooper Henderson, 1803–1877, British, Mail Coaches on the Road: the Louth-London Royal Mail progressing at Speed, between 1820 and 1830, Oil on canvas, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B2001.2.4

Richard Gilson Reeve, 1803–1889, after James Pollard, 1792–1867, British, The Mail Coach in a Drift of Snow, Hand colored etching and aquatint on wove paper, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1996.16.16

Charles Hunt, 1803–1877, British, after Samuel John Egbert Jones, active 1820–1845, British, Royal Mails, Starting from the Post Office, Lombard Street, Aquatint, hand-colored, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.16713

Thomas Rowlandson, 1756–1827, British, after Augustus Charles Pugin, 1762–1832, French, The Post Office, 1809, Aquatint, hand-colored, Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, B1977.14.16710

A Postboy with Mailbags, An Alarm by the Guard, Calling for the Squire’s Mailbag, these illustrations by Hugh Thomson are taken from my own copy of Coaching Days and Coaching Ways

Wow, what an interesting post. Thank you so much for sharing that. I used to collect stamps as a child. It’s interesting how the improvements of the roads was brought about by the need to get letters delivered rather than the other way round.

Thanks,Paula, I’m glad you enjoyed my brief look at the history of mail coaches. It’s amazing how things we wouldn’t normally connect, like roads and mail are so dependent on each other – well, they were until the advent of electronic mail!

Still need parcel post though 📦

I wonder how long it will be until parcels are delivered by drone? 🙂